Cats infected with bird flu are falling under the radar when it comes to tracking and managing the virus, and this must change rapidly, scientists warn in a new paper.

The emergence of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (H5N1) in the US has put poultry and dairy farms on high alert, resulting in culls that are devastating the industries, and fears it could transform into a human pandemic.

We've seen reports of infections in cats, but new research from the University of Maryland in the US suggests feline cases – and the risk of transmission from cats to humans – is not being taken seriously enough.

"Bird flu is very deadly to cats, and we urgently need to figure out how widespread the virus is in cat populations to better assess spillover risk to humans," University of Maryland airborne infectious disease researcher Kristen Coleman says.

This is particularly crucial as birds in the United States make their springtime migrations, potentially spreading the virus further afield.

"As summer approaches, we are anticipating cases on farms and in the wild to rise again," Coleman adds.

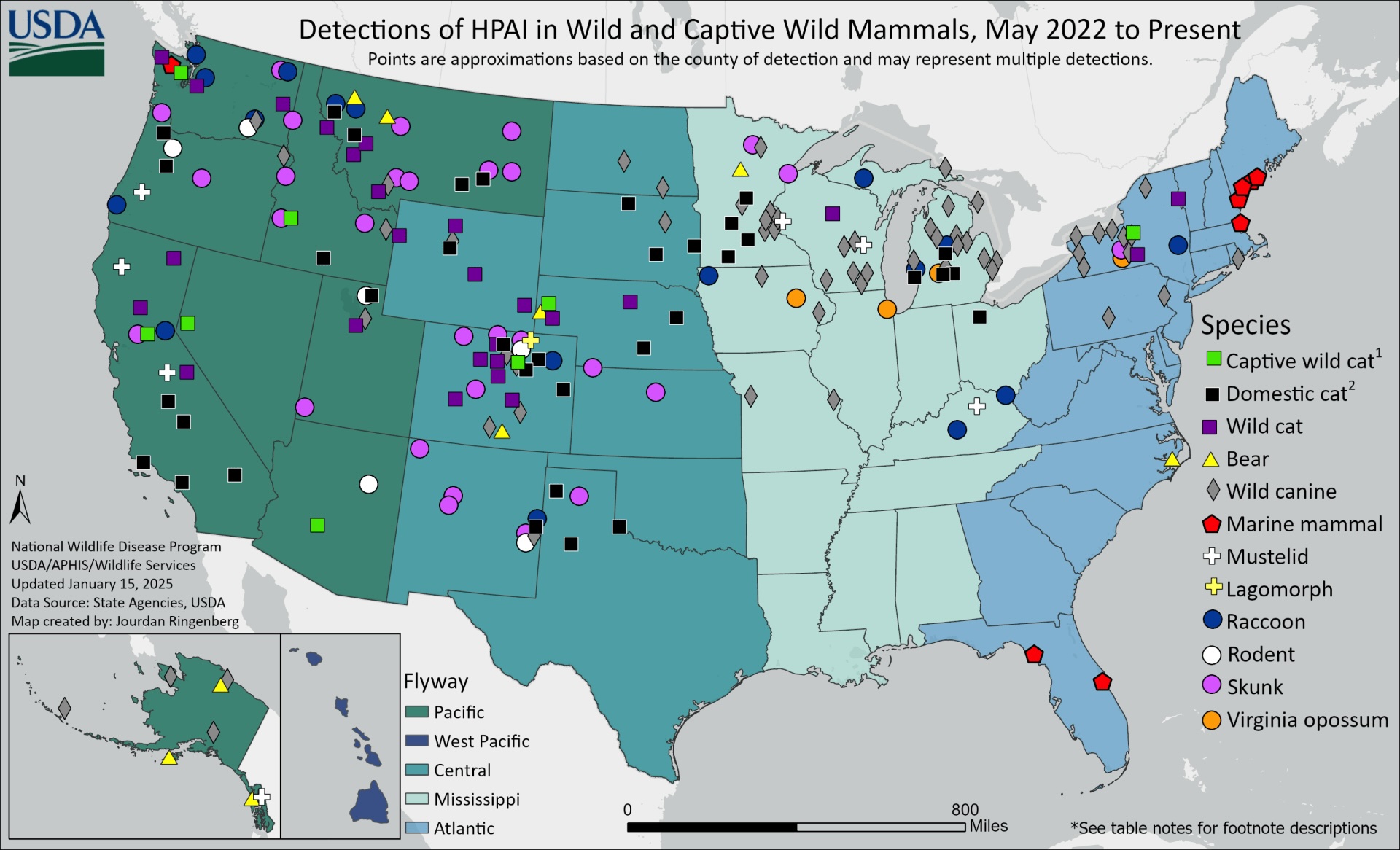

Coleman and her co-author, animal scientist Ian Bemis, analyzed peer-reviewed research published between 2004 and 2024, finding 607 reported cases of bird flu infection in cats globally. Across 18 countries and 12 species (ranging from house cats to zoo tigers), 302 deaths were associated with the virus.

The researchers believe that a lack of monitoring means these numbers are a serious underestimation.

They noticed that in 2023, reports of pet cat infections increased drastically. In 2023 and 2024, there was a spike in the number of pet cats infected with, and killed by, bird flu.

Most cases can be attributed to the deadliest strain of bird flu, H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b, which had a 90 percent case fatality rate within the data. However, this rate may not reflect the actual risk of death to cats if infected, since testing has been very limited.

The authors urge authorities, veterinarians, and pet owners to increase surveillance of cats.

"We want to help protect both people and pets," Coleman says.

There are no confirmed cases of cat-to-human transmission for this particular strain of bird flu, although in 2016, the outbreak of a different strain among cats in New York City animal shelters did result in cat-to-human transmission.

Human-to-human transmission is yet to be recorded, but researchers are concerned this ability may only be a few genetic mutations away.

Nonetheless, Coleman and Bemis note that owners of farm cats, free-roaming cats, veterinarians, zookeepers, and animal shelter volunteers may have a higher risk of exposure to bird flu through interspecies transmissions.

Hunting is in a cat's nature. A free-range cat can kill around 186 animals each year. Besides protecting wildlife and saving on vet bills, this might be another good reason to transition your beloved companion to an indoor lifestyle.

Cats become infected by hunting and eating infected wild birds and mammals, or by consuming infected raw pet food or raw cow's milk – including products sold commercially. They can also catch the virus from other mammals they live alongside, including cats in the neighborhood and, potentially, their owners.

"Our future research will involve studies to determine the prevalence of high pathogenicity avian influenza and other influenza viruses in high-risk cat populations such as dairy barn cats," Bemis says.

The research is published in Open Forum Infectious Diseases.