According to a new study, humans can inhale more than 70,000 microplastic particles each day in an indoor environment – far more than previously thought. Worse still, most of them are small enough to penetrate deep into our lungs.

Plastic is one of the defining environmental issues of our time, clogging up everything from our waterways to our bloodstreams. Tiny particles of the stuff enter our bodies not just through what we eat and drink but through the very air we breathe.

Related: You Inhale a Credit Card of Plastic Every Week. Here's Where It Goes.

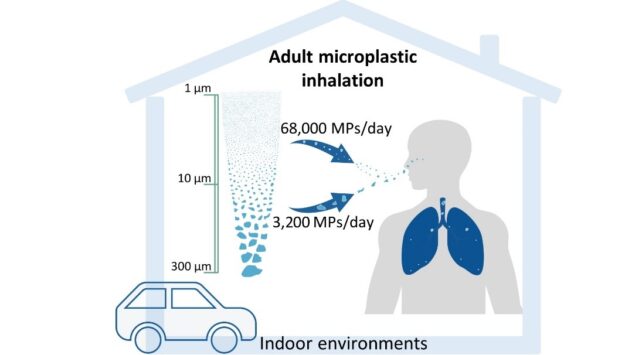

In a new study, scientists from the Université de Toulouse in France quantified just how much plastic dust we may be inhaling every day. The team took 16 indoor air samples from their own apartments and cars, then analyzed them using a technique called Raman spectroscopy to measure the concentration of microplastics floating around in there.

And, it turns out, it's a lot. The median concentration for apartment air samples were 528 microplastic particles per cubic meter, and a whopping 2,238 particles per cubic meter in cars. Of those particles, 94 percent were less than 10 micrometers wide, which is small enough to work their way deep into lung tissue when inhaled.

From this and other research, the team estimated that adults inhale roughly 71,000 microplastic particles from these environments every single day, with 68,000 of them being sub-10 micrometers.

"The concentration we found is 100-fold higher than previous extrapolated estimates," the authors say.

"People spend an average of 90 percent of their time indoors, including homes, workplaces, shops, transportation, etc., and all the while they are exposed to microplastic pollution through inhalation without even thinking about it."

Exactly what those microplastics get up to once they're in our bodies remains uncertain, but scientists suspect it's nothing good. Recent studies suggest they could increase the risk of certain cancers, fertility issues, stroke, and a range of other health problems.

More research is desperately needed to investigate the biological effects of microplastics, as well as ways we might be able to reduce exposure.

The research was published in the journal PLOS One.