The borderlands of black holes ought to be chaotic spaces where the rate at which matter is drawn across into oblivion is held back only by the blinding fury of radiation spilling away from the edge of darkness.

This zone is considered to be unstable, prone to flares, jets, and outbursts. Yet, predicting these dynamic events can be complicated, with mathematically accurate descriptions of the warped space and extreme physics surrounding proving a challenge.

A new modeling study led by researchers from the Flatiron Institute in the US now provides the most detailed simulations to date of how stellar-mass black holes gobble up and spew out matter at varying rates.

Related: What if a Tiny Black Hole Shot Through Your Body? A Physicist Did The Math

Crucially, the study didn't rely on simplifications used in earlier models. Those shortcuts have previously been required just to make the calculations possible, but here the simulations were based on much more complex data.

Using two powerful supercomputers to combine survey observations of black hole accretion flows with measures of their spin and magnetic field, the team developed a new model that describes the movement of gas, light, and magnetism around black holes little bigger than our own Sun.

"This is the first time we've been able to see what happens when the most important physical processes in black hole accretion are included accurately," says astrophysicist Lizhong Zhang, from the Flatiron Institute.

"These systems are extremely nonlinear – any over-simplifying assumption can completely change the outcome."

The new simulations align with observations of various kinds of black hole systems. While detailed images of supermassive black holes are now possible, light from smaller objects still needs to be teased apart in order for astronomers to map the distribution of their energy.

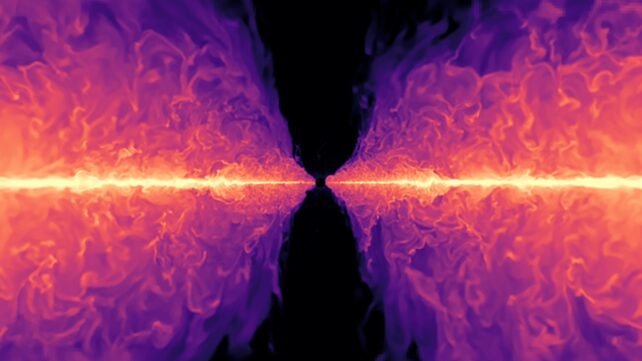

By attracting enough material, the researchers showed, black holes accumulate thick accretion disks that absorb significant amounts of radiation, releasing the energy instead through winds and jets.

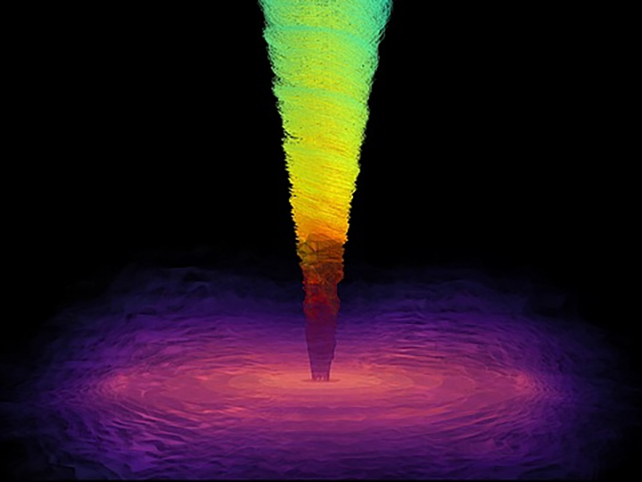

Their simulations of these ravenous black holes also showed how a narrow funnel forms, which slurps up material at astonishing rates and creates a beam of outgoing radiation that can only be observed on certain, favorable viewing angles.

The team also found that the configuration of the surrounding magnetic field can play a significant role in the black hole's behavior, helping to guide the flow of gas towards its horizon and out again in the form of winds and jets.

"Ours is the only algorithm that exists at the moment that provides a solution by treating radiation as it really is in general relativity," says Zhang.

The simulation incorporates Einstein's general theory of relativity, which describes how masses distort space and time, plus detailed models covering the laws of physics that govern plasma gas, magnetic fields, and the way light interacts with matter.

"Our methods capture the propagation of photons in curved spacetime accurately, and when coupled to the fluid converges to known solutions for linear waves and shocks," the researchers write.

Next, the researchers want to see if their simulations might also apply to other types of black holes, including the Sagittarius A* supermassive black hole at the center of our own Milky Way.

They also suggest that their simulations could help solve the mystery of the recently discovered 'little red dots', which emit less X-ray radiation than expected.

"While our models use opacities appropriate for stellar-mass black holes, it is likely that many general features of our results will also apply to accretion onto supermassive black holes as well," the researchers write.

The research has been published in The Astrophysical Journal.