If there's a man in the Moon, as the old beliefs go, he's a pretty venerable one. Earth's lunar companion is thought to have formed not long after the planet itself, some 4.4 billion years or so ago, when the Solar System was young.

It was then, according to theory, that a Mars-sized object smacked into Earth, which was still warm and squishy and newly formed, and broke off a huge cloud of debris that coalesced into the Moon in Earth's orbit.

But the Moon's youthful good looks are apparently deceptive. A new study of tiny grains of zircon in Apollo lunar samples suggests that it's even older than we thought, by a good 40 million years.

That means that the Moon is at least 4.46 billion years old, says a team led by geologist Jennika Greer, now at the University of Glasgow – just a hair younger than Earth, which is an estimated 4.54 billion years old.

"These crystals are the oldest known solids that formed after the giant impact," says cosmochemist Philipp Heck of the Field Museum and University of Chicago. "And because we know how old these crystals are, they serve as an anchor for the lunar chronology."

It's unknown precisely how the Moon formed and when, but the presence of some specific elements strongly suggests a terrestrial origin. The giant impact hypothesis is the current favorite, sometime in the early Solar System, when astronomers expect a much higher number of large objects and protoplanets flying around and smacking into each other.

Estimates have varied on when this giant impact took place, but a growing body of evidence, based on dating of lunar samples, suggests that it was much earlier than initial suppositions of around 4.4 billion years ago, with some analyses suggesting it formed as early as 4.51 billion years ago.

Zircon crystals are an excellent way to trace the age of a sample because of a quirk of the way they form. When they are forming, zircon crystals incorporate uranium, but strongly reject lead. Over time, the radioactive uranium in the zircon decays into lead at a very well understood rate. Scientists can look at the ratios of uranium to lead in a zircon crystal and work out how long ago the zircon formed, with a high level of accuracy.

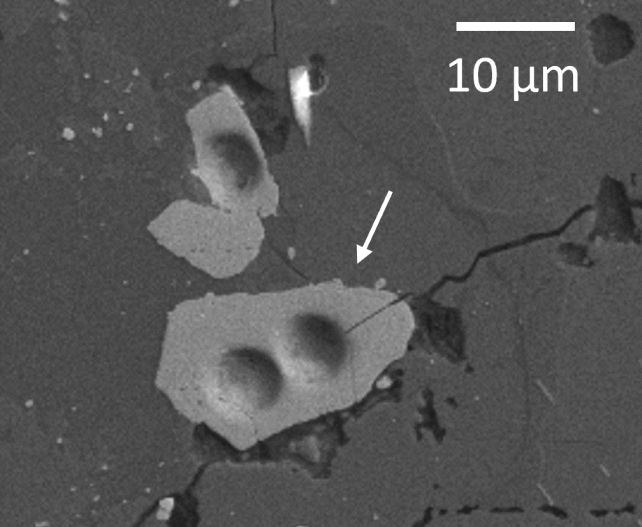

These microscopic crystals can be found in samples of Moon dirt retrieved during the Apollo era from the lunar sample. Greer and her colleagues studied zircon found in samples from Apollo 17, the last lunar mission, which took place in 1972. These crystals, the team says, must have formed after the Moon's surface solidified, from the molten global ocean that covered it immediately following its formation.

"When the surface was molten like that, zircon crystals couldn't form and survive. So any crystals on the Moon's surface must have formed after this lunar magma ocean cooled," says Heck. "Otherwise, they would have been melted and their chemical signatures would be erased."

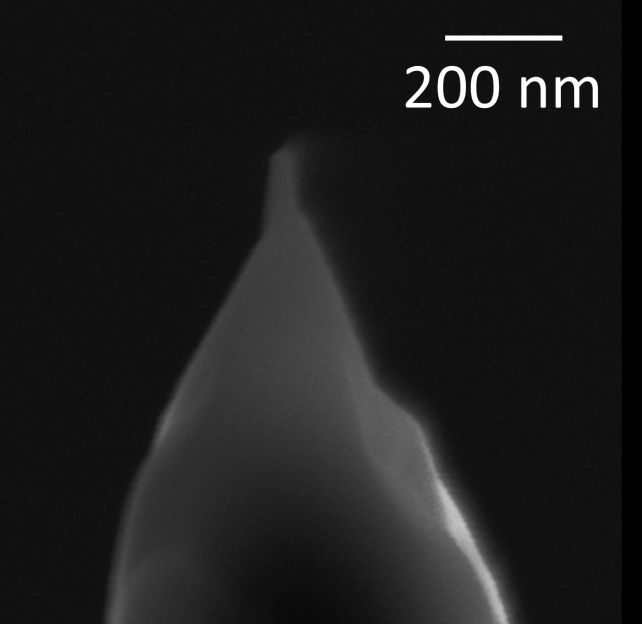

The researchers used atom probe tomography to study the composition of their samples, sharpening the crystals to a point, then using lasers to evaporate atoms from the point. A mass spectrometer analyzed the vaporized material to measure how heavy it was, which allowed the scientists to determine the ratios of uranium to lead.

In turn, this showed that the age of these specific crystals was 4.46 billion years old. Which means that the Moon must be at least that old. This information could help scientists determine other aspects of the Moon's history, such as how long it took to form and solidify, and better estimate the date for the giant impact.

"It's amazing being able to have proof that the rock you're holding is the oldest bit of the Moon we've found so far. It's an anchor point for so many questions about the Earth," Greer says. When you know how old something is, you can better understand what has happened to it in its history."

The research is due to be published in Geochemical Perspectives Letters.