In the Peruvian Andes, thousands of years ago, humans were making liberal use of psychoactive drugs.

We know this for a fact: For the first time, direct chemical evidence of these drugs has been found, in residual traces left on the paraphernalia used for their consumption. It's the earliest known human use of psychoactive drugs in the Andes.

That use was by a culture known as the Chavín who inhabited the region during the Middle-Late Formative Period between around 1200 and 400 BCE, before the rise of the Incan Empire.

What's even more interesting is that it seems to have been a pastime of only the cultural elite, since the bone tubes used to imbibe the drugs were found in private chambers that only a few people could enter at a time.

"Taking psychoactives was not just about seeing visions," says anthropological archaeologist Daniel Contreras of the University of Florida. "It was part of a tightly controlled ritual, likely reserved for a select few, reinforcing the social hierarchy."

Human shenanigans are not a new phenomenon. We've been tattooing ourselves, modifying our bodies, and enjoying mind- and mood-altering substances for thousands of years. Nowadays, the use of psychoactive drugs is broadly frowned upon, but in eons past, very different cultural contexts were at play.

From various global archaeological sites around the world, scientists have found evidence of the use of psychoactive substances dating back thousands of years. In South America, these substances are hypothesized to have played an important role in rituals around the Middle-Late Formative Period, but evidence has been scarce.

Recently, at the ancient ceremonial site of Chavín de Huántar in the Andes, archaeologists found 23 artifacts – mostly bone tubes – that have been linked to the use of psychoactive substances elsewhere in the region. Led by archaeologist John Rick of Stanford University, a team of scientists set about investigating what they were.

They took samples from the 23 artifacts – 22 made of bone and one of mollusk shell – and subjected them to organic chemical residue analysis to try to identify what the substances were. On some of the artifacts were clear traces of wild tobacco (Nicotiana) and vilca (Anadenanthera colubrina var. cebil), which contains a hallucinogen related to DMT.

The team also identified damage to the starch grains recovered from the interiors of the tubes that was consistent with dry heat – suggesting that the nicotine roots and vilca beans were dried, roasted, and powdered as preparation for inhalation.

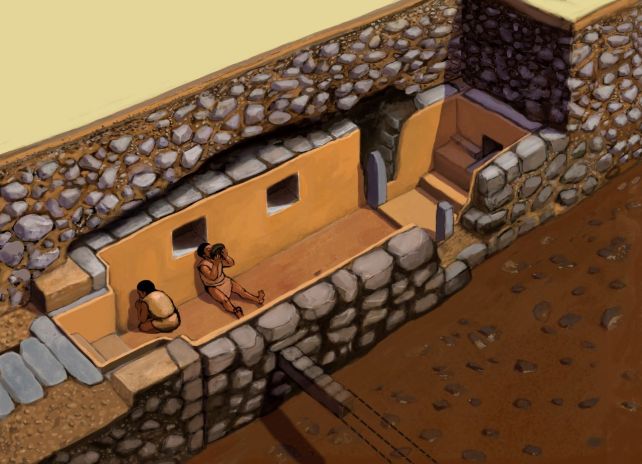

The context in which the tools were discovered is strongly suggestive of exclusivity, the researchers say. They were found in a rectangular chamber that was built early in the first millennium BCE, around 3,000 years ago, and was completely sealed in around 500 BCE. It remained undisturbed until recent excavations.

The chamber was pretty small, and would have had restricted access. It also contained artifacts, such as ceramic vessels, that could be associated with ceremonial activity. Other, similar chambers had similar artifacts, including a chamber that also contained bone tubes.

Put together, this evidence suggests that the use of psychoactive substances was an important part of ritual activity at Chavín de Huántar, and that access to the spaces wherein it was conducted was also restricted.

It's a discovery that helps researchers understand how Chavín de Huántar, a large, grand monument at high altitudes over 3,000 meters (10,000 feet) came to be built, and the role it played in the transition from more egalitarian societies that existed before to the rigidly hierarchical systems that came after.

"The supernatural world isn't necessarily friendly, but it's powerful. These rituals, often enhanced by psychoactives, were compelling, transformative experiences that reinforced belief systems and social structures," Contreras explains.

"One of the ways that inequality was justified or naturalized was through ideology – through the creation of impressive ceremonial experiences that made people believe this whole project was a good idea."

Times have changed, indeed.

The research has been published in PNAS.