An experimental philosopher from the University of Arizona has set up what he's calling the Millennium Camera: a device designed to take a single image of the Tucson, Arizona landscape over the course of a thousand years.

Creator Jonathon Keats says he wants the Millennium Camera to provoke deeper thought about the past, present, and future of humanity – and what our society might look like by the time we get into the 31st century.

"Most people have a pretty bleak outlook on what lies ahead," says Keats. "It's easy to imagine that people in 1,000 years could see a version of Tucson that is far worse than what we see today, but the fact that we can imagine it is not a bad thing."

"It's actually a good thing, because if we can imagine that, then we can also imagine what else might happen, and therefore it might motivate us to take action to shape our future."

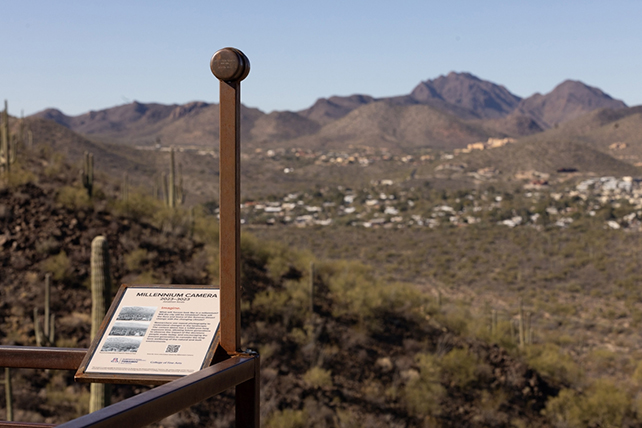

The camera comprises a steel pole with a copper cylinder on top. As light enters the cylinder, it goes through a pin-sized hole in a thin sheet of 24-karat gold, then on to a surface treated with an oil paint pigment called rose madder.

Keats could only make an educated guess on the kind of material that would change gradually enough over the course of centuries to leave a recognizable image, but hopes the rose madder pigment's fading in the repeated cycles of daylight does the trick.

Set near a hiking trail on Tumamoc Hill, overlooking Tucson, the camera is accompanied by a notice that encourages passers by to reflect on what the next millennium might hold.

When the picture is finally revealed, the most static parts of the landscape will look the clearest, while areas that have regularly changed will take on more ghostly forms.

What's most likely is that the outline of the natural landscape will be strongly imprinted, while the number and design of the buildings in the shot will change over the centuries – though the camera project is neutral in terms of forward planning.

"By no means is the camera making a statement about development – about how we should build the city or not going forward," says Keats. "It is set there to invite us to ask questions and to enter into conversation and invite the perspective of future generations in the sense that they're in our minds."

What life will look like in a thousand years is hard to imagine, though it's an interesting thought experiment. If you go back a millennium, we were still in the Middle Ages, fighting our battles with swords and axes.

By the time another thousand years have passed, climate change, AI technology, and many other factors will no doubt have changed our world in ways that mean it's very different from today.

Keats admits that there are "so many reasons" why the Millennium Camera might not work as intended: no one has built a camera like this before, and it could even be removed by future generations. However, the intention is to keep it in operation until 3023.

"If we open in the interim, then it diminishes the imagining that we need to be doing," says Keats.