An organic compound used in the manufacture of plastics has been detected in the atmosphere of Saturn's largest moon, Titan.

While polymers of the chemical vinyl cyanide have plenty of uses on Earth in making acrylic garments and tent fabric, it's feasible that under conditions on Titan they could form flexible structures similar to our own cell membranes.

Previous studies of Titan's upper atmosphere had already provided some strong hints of the presence of the molecule C2H3CN (called acrylonitrile or vinyl cyanide), but NASA scientists have now confirmed it using collected by the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile.

Produced synthetically on Earth by converting the hydrocarbon methyl ethylene (or propene), units of the molecule are strung together to form polymers or mixed with other chemicals to make fibres used in clothing, sails, and weather-proof materials.

Titan's mix of hydrocarbons in an atmosphere awash with clouds of cyanide would theoretically do the same job. And now we have proof.

"We found convincing evidence that acrylonitrile is present in Titan's atmosphere, and we think a significant supply of this raw material reaches the surface," says lead researcher Maureen Palmer from NASA's Goddard Space Flight Centre.

For space enthusiasts and alien hopefuls, Titan is the flavour of the decade.

Under the watchful eye of Cassini's space probe combined with data from Earth-based telescopes, researchers have discovered in recent years that the moon has a thick nitrogen atmosphere and a weather cycle based on evaporation and pooling of liquid hydrocarbons.

It might be a slightly chilly -179o Celsius (-290o Fahrenheit) on Titan's surface, and not a lot of oxygen, but it hasn't stopped plenty of speculation on the possibility that its complex chemistry could have some life-like features.

One of the properties of life on Earth is the partitioning of biochemistry into fat-lined bubbles we call cells.

The fat molecules, or phospholipids to be precise, form a double-layer that concentrates the chemical soup we think of as biology and helps protect them from the environment.

"The ability to form a stable membrane to separate the internal environment from the external one is important because it provides a means to contain chemicals long enough to allow them to interact," says researcher Michael Mumma, director of the Goddard Centre for Astrobiology.

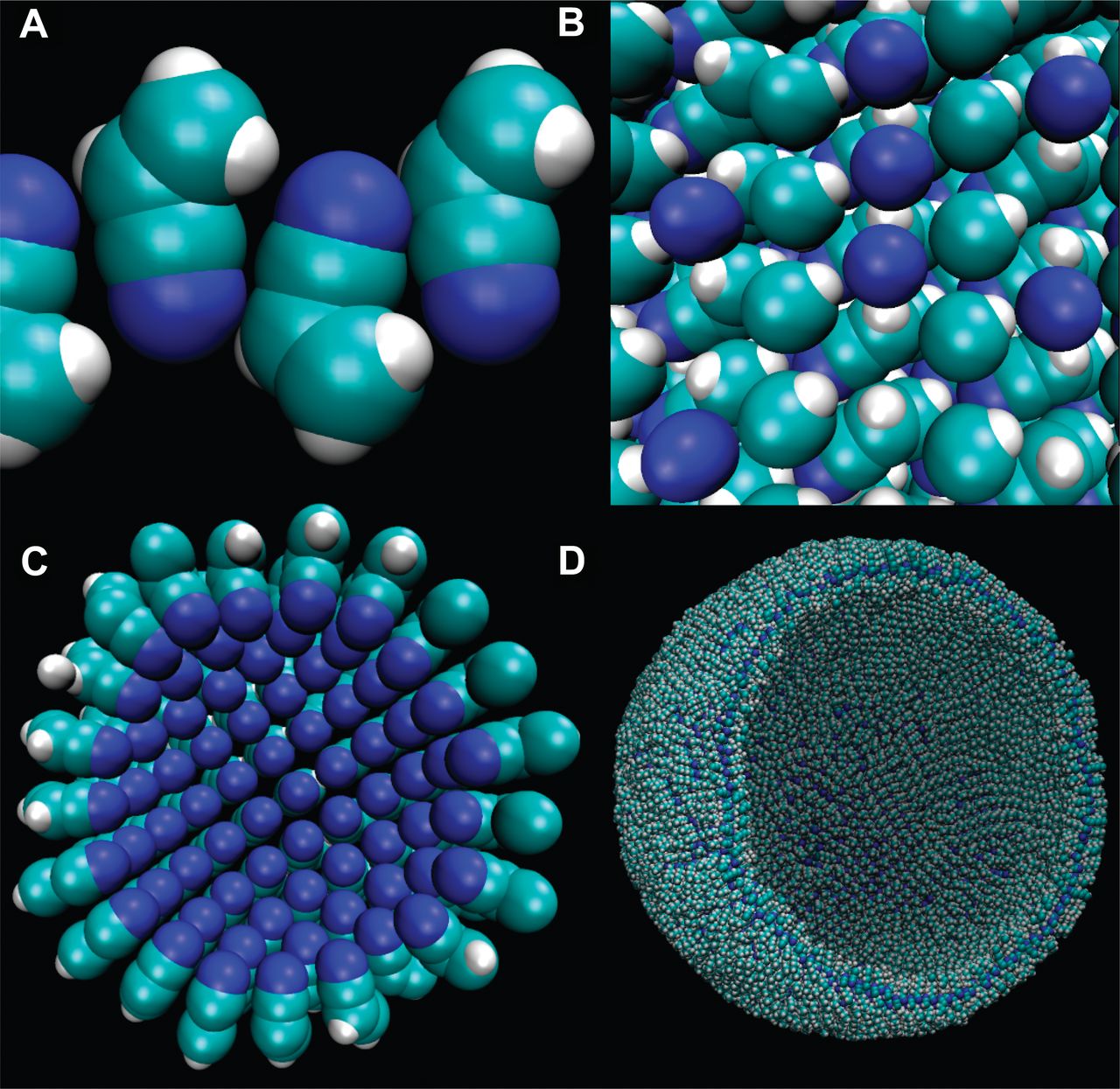

Titan's conditions rule out production of these kinds of lipids, but several years ago students from Cornell University proposed similar membranes could be made out of nitrogen-based compounds such as vinyl cyanide.

These 'azotosomes' – a word based on the French word for nitrogen, azote – could self-assemble into sheets that pull into bubbles much like our own cell's phospholipids.

James Stevenson, Jonathan Lunine, Paulette Clancy/Science Advances 2015

James Stevenson, Jonathan Lunine, Paulette Clancy/Science Advances 2015

There's still a world of difference between a bubble and what physicist Freeman Dyson once referred to as the "garbage bag model", where some sort of replicating chemistry churns away inside a protective membrane.

But the confirmation of C2H3CN molecules in Titan's stratosphere at concentrations of 2.8 parts per billion means we can still stay excited about the possibility of some sort of biology-like chemistry.

The researchers used archival data from ALMA collected over several months in 2014 to search for signature light emissions bouncing off Titan's atmosphere.

The chemical's abundance makes it possible it could condense in the lower parts of the atmosphere and make it to the surface in the precipitation, where it could accumulate in the moon's lakes.

By the team's estimates, there could be enough vinyl cyanide floating around in Titan's Ligeia Mare to have a concentration of about 10^7 membranes per cubic centimetre.

The next step would be for researchers to try to make vinyl cyanide azotosomes in a laboratory and study how it behaves under Titan's conditions.

Even if we never find creepy-crawlies made of vinyl writhing sluggishly in the depths of Ligeia Mare, discovering chemistry hovering on the verge of biology would be incredibly exciting.

This research was published in Science Advances.