An ancient jawbone previously thought to have belonged to a Neanderthal may force a rethink on the history of modern humans in Europe.

A new analysis of the broken mandible reveals that it has nothing in common with other Neanderthal remains. Rather, it could belong to a Homo sapiens – and, since it's dated to between 45,000 to 66,000 years ago, might be the oldest known piece of our species' anatomy on the European continent.

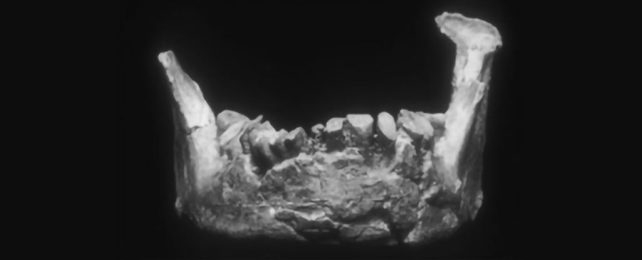

The bone itself was found in 1887 in the town of Banyoles in Spain, for which it is nicknamed. Since then, scientists have studied it pretty extensively, dating it to a timeframe in the Late Pleistocene when the region that is now Europe was predominantly populated by Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis).

This, and the archaic shape of the bone, led scientists to the conclusion that Banyoles in fact belonged to a Neanderthal.

"The mandible has been studied throughout the past century and was long considered to be a Neandertal based on its age and location, and the fact that it lacks one of the diagnostic features of Homo sapiens: a chin," says palaeoanthropologist Brian Keeling of Binghamton University in the US.

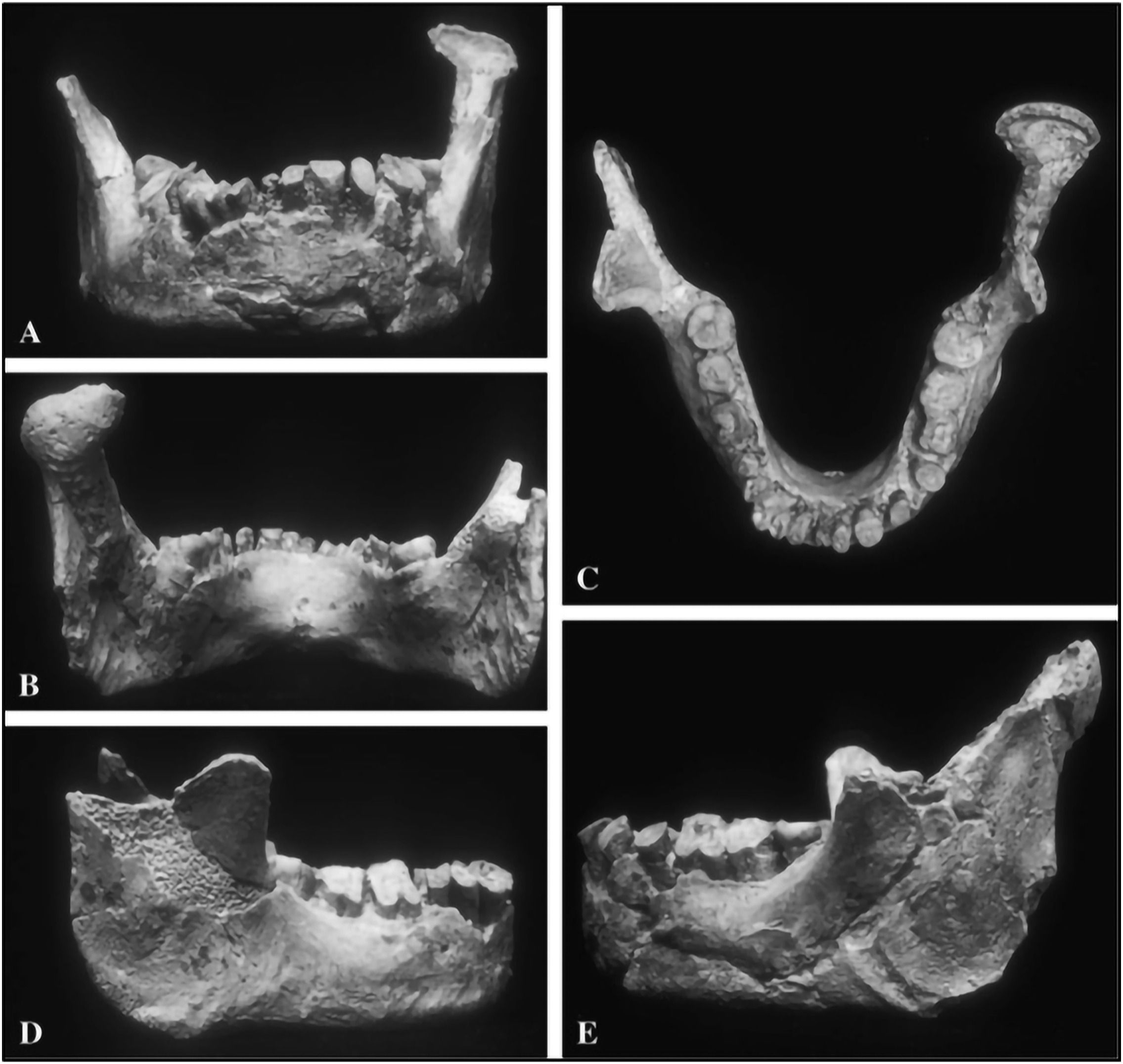

Keeling and his colleagues undertook a thorough investigation of the bone using a process called three-dimensional geometric morphometric analysis. This is a non-invasive protocol that involves going over the shape of a bone in exhaustive detail, mapping its features and comparing them to other remains.

They took high-resolution 3D scans, and used these not just to study the bone, but to reconstruct the missing pieces. Then they compared Banyoles to the mandibles of Neanderthals and modern humans.

"Our results found something quite surprising," Keeling says. "Banyoles shared no distinct Neanderthal traits and did not overlap with Neanderthals in its overall shape."

It seemed more consistent with the jawbones of our own branch of the family tree, except for one detail: the absent chin.

Since a chin is considered a defining feature of Homo sapiens compared to other archaic humans, this presented a problem. In addition, Banyoles also shared features with ancient hominins that inhabited Europe hundreds of thousands of years ago.

The researchers compared the bone to one from an early modern human from around 37,000 to 42,000 years ago whose remains were found in Romania. It's known for having Neanderthal features, but also has a chin.

DNA analysis of that jawbone showed the DNA included sequences from a single Neanderthal ancestor who lived four or six generations prior – which likely explains its mixed features.

Since Banyoles doesn't have Neanderthal features, the team concluded that its strange shape is unlikely to be because the individual was a hybrid.

Comparison with earlier Homo sapiens bones from Africa showed that these individuals had less pronounced chins than we do now.

So there are two possibilities. Either Banyoles was a Homo sapiens from a previously unknown group that coexisted with Neanderthals in Late Pleistocene Europe. Or it was a hybrid between Homo sapiens of this unknown group and a yet-to-be-identified ancient human.

Only one thing is known for sure: that Banyoles was not a Neanderthal.

There is one way to resolve the mystery, the researchers say – try to extract some DNA from the bone or one of the teeth, and sequence it.

"If Banyoles is really a member of our species, this prehistoric human would represent the earliest Homo sapiens ever documented in Europe," Keeling says.

The research has been published in the Journal of Human Evolution.