Some dinosaurs were scaly, some were covered in bony plates of armor, and others were even feathered. But now paleontologists have discovered a new species with a type of skin covering that's never been seen in dinosaurs before: hollow spikes.

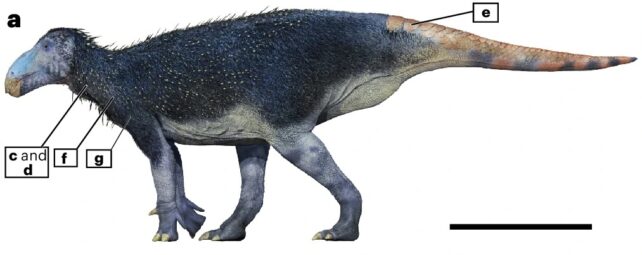

Discovered in northeastern China, the new species has been named Haolong dongi. That means "spiny dragon," and it's not hard to see why: While most of its iguanodontian relatives are scaly, Haolong looks like it's wearing a fur coat made of porcupine skin.

The spikes are concentrated around its neck, back, and sides, run parallel to each other, and all point towards the dinosaur's rear. Most are small, around 2 to 3 millimeters long, but interspersed among them are medium-sized spikes measuring 5 to 7 millimeters. A few are much bigger, with the longest stretching more than 44 millimeters.

Haolong is known only from a single specimen – an almost complete skeleton stretching 2.45 meters (8 feet) long, with stunningly preserved skin. Intriguingly, the bones suggest it was still a juvenile when it died, so the scientists can't be sure whether the spikes were a feature of adults too or were shed as the animal grew.

Their purpose is also unclear, but the researchers run through a series of intriguing possible explanations.

At a glance, the spikes look suspiciously similar to early protofeathers that other dinosaurs sported – but the researchers point out that these had already been established well before Haolong came along some 125 million years ago.

There's a chance they were there to help keep the animal warm. It lived in a relatively cool climate, and other dinosaurs in its environment, like Yutyrannus, wore thick feather coats that probably helped regulate their body temperature. But the spikes might not have been dense enough for that purpose in Haolong.

Were they for visual display or camouflage, then? The team can't be sure of that either, because no sign of pigment cells was found.

Maybe they were sensory organs? They do look a little like the tiny spinule structures that some living lizards and snakes use to sense touch and vibrations. But no, the researchers say Haolong's spikes seem too big, and don't connect to its scales quite right.

The most likely explanation, the scientists hypothesize, is that they were there to deter predators. Haolong's home turf was full of relatively small carnivores, so this kind of defensive system could have evolved to deal with those pressures.

The spikes probably weren't strong enough to do much harm to, let alone kill, an attacking predator – but they might have been sufficiently annoying to make almost any other animal look like a more enticing meal.

Related: Exceptionally Preserved 'Dinosaur Mummies' Reveal First-Known Reptile Hooves

"These defences did not necessarily provide impenetrable protection against theropod teeth and claws, but they made the prey more difficult and time-consuming to kill and ingest and consequently reduced the likelihood of successful ingestion," the researchers write.

Whatever Haolong was doing with its spikes, the discovery shows that the weird world of dinosaurs still has plenty of surprises for us to find.

The research was published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution.