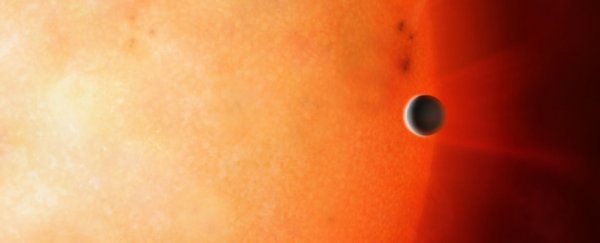

Some 730 light-years away, around a star that's a lot like our Sun, astronomers have found a really weird exoplanet.

It's just a little smaller than Neptune, which could indicate a gaseous planet… but it's more than twice as massive as Neptune, with a density comparable to Earth and Venus.

This super-dense surprise suggests that the exoplanet is rocky, but well above the usual upper size limit for rocky planets. Which, in turn, means it could be something very rare indeed - what is known as a Chthonian planet, a core of a gas giant that had its atmosphere stripped away.

This is a hypothetical class of planets, as detection of one has never been confirmed before.

The planet in question is called TOI-849b, and it's orbiting a Sun-like star called TOI-849. When we figure out exactly what it is, it could help us to better understand what's inside the thick atmospheres of gas and ice giants, like Neptune, and the formation processes of these formidable planets.

"TOI 849 b is the most massive terrestrial planet - that has an Earth-like density - discovered. We would expect a planet this massive to have accreted large quantities of hydrogen and helium when it formed, growing into something similar to Jupiter," said astronomer David Armstrong of the University of Warwick in the UK.

"The fact that we don't see those gases lets us know this is an exposed planetary core. This is the first time that we've discovered an intact exposed core of a gas giant around a star."

TOI-849b was located by a survey conducted using NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), the exoplanet-hunting space telescope. TESS searches for exoplanets by staring at stars, using its sensitive instruments to look for regular, faint dips in their light that indicate something big, like a planet, is passing in front of the star.

How much and how often the light of the star dims allows astronomers to calculate things like how big the planet is, and how close it is to the star. TOI-849b is very close to its star - it whips around every 18 hours. Such a close proximity would make it extremely hot, with a surface temperature of around 1,800 Kelvin (1,530 degrees Celsius, or 2,780 degrees Fahrenheit).

This close proximity to the host star puts the exoplanet in a special category - very few Neptune-sized planets have been found close to their stars, creating what is called a hot Neptune desert.

This alone would be noteworthy, but then the team did follow-up observations using Doppler spectroscopy.

When a planet orbits a star, it exerts a slight gravitational tug on the star, which causes the star to wobble a little on the spot. Doppler spectroscopy measures the way the star's light changes as it wobbles. If the mass of the star is known, astronomers can calculate the mass of the planet based on how much the star wobbles.

This is how the team calculated the exoplanet's mass - around 39.1 times the mass of Earth, and 2.3 times the mass of Neptune. This results in a density of 5.2 grams per centimetre cubed - very close to Venus' 5.24 g/cm³ and Earth's 5.51 g/cm³.

"While this is an unusually massive planet, it's a long way from the most massive we know," Armstrong explained.

"But it is the most massive we know for its size, and extremely dense for something the size of Neptune, which tells us this planet has a very unusual history. The fact that it's in a strange location for its mass also helps - we don't see planets with this mass at these short orbital periods."

Which leads to the conclusion that we're looking at a Chthonian planet. Although how it got that way is still a mystery.

It's possible that TOI-849b formed with a huge gaseous atmosphere similar to that of Jupiter that was later stripped away somehow.

We know that gas planets next to their stars can have their atmospheres stripped away by the incredible heat. And one of the only other hot Neptunes ever discovered, Gliese 3470 b, is losing its atmosphere at an incredible rate, evaporated by the heat of its star.

This process wouldn't account for the entirety of the atmosphere loss calculated for TOI-849b, but other events could have played a role, such as collisions with other large objects.

The other option is that TOI-849b started forming as a gas giant, but didn't have enough material - either because it formed late in the evolution of the planetary system, when there was very little material left in the star's protoplanetary disc, or because it formed in a gap in the disc, where there wasn't enough material to accrete an atmosphere.

The team plans to follow up their research with observations to try and determine if TOI-849b has any atmosphere left. This could help determine the composition of the core itself.

"One way or another, TOI 849 b either used to be a gas giant or is a 'failed' gas giant," Armstrong said.

"It's a first, telling us that planets like this exist and can be found. We have the opportunity to look at the core of a planet in a way that we can't do in our own Solar System. There are still big open questions about the nature of Jupiter's core, for example, so strange and unusual exoplanets like this give us a window into planet formation that we have no other way to explore."

The research has been published in Nature.