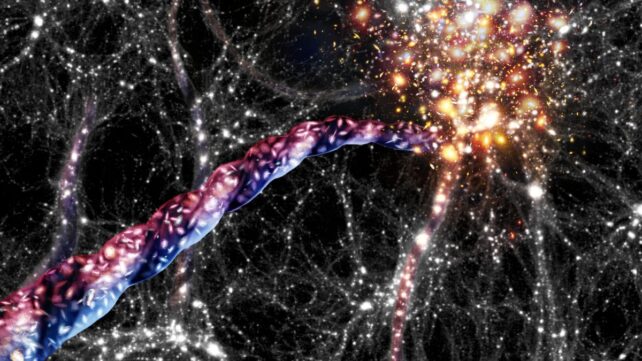

A team of astronomers studying the distribution of galaxies in nearby space has discovered something truly extraordinary: a huge strand of galaxies, twisting around as though caught up in a slow-motion cosmic tornado.

It's at least 49 million light-years in length – representing the single longest rotating filament ever found in the Universe, a vast vortical strand of the cosmic web.

It's one of the largest spinning structures we've ever seen, recording the way the cosmic web shapes the Universe and even imprints its mark on the galaxies that fill it.

"What makes this structure exceptional is not just its size, but the combination of spin alignment and rotational motion," says physicist Lyla Jung of the University of Oxford in the UK.

"You can liken it to the teacups ride at a theme park. Each galaxy is like a spinning teacup, but the whole platform – the cosmic filament – is rotating too. This dual motion gives us rare insight into how galaxies gain their spin from the larger structures they live in."

Related: Astronomers Uncover a Massive Shaft of Missing Matter

The cosmic web is basically the invisible backbone of the Universe – a massive, complicated network made up of countless filaments of dark matter, gravitationally binding the Universe and controlling the way galaxies are distributed and move around.

Its strands are like cosmic highways along which galaxies congregate and travel; studying it reveals the vast, overarching metastructure of the Universe, giving us information about how it all hangs together, and how it evolved from the first moments after the Big Bang.

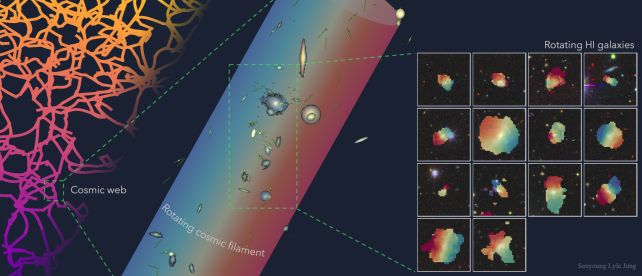

Led by Jung and her co-lead, physicist Madalina Tudorache of Oxford and the University of Cambridge, a team of researchers first spotted this particular filament in observations taken using the MEERKat radio telescope in South Africa as part of the MIGHTEE sky survey.

Some 440 million light-years away – a mere hop, step, and jump in cosmic terms – they spotted 14 galaxies behaving peculiarly. They appeared to be arranged in a curiously straight, needle-thin line measuring about 117,000 light-years across and 5.5 million light-years long, with too many of them oriented in the same way to be attributed to chance.

This obviously warranted further investigation. The researchers turned to data collected by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, which covers a wider field of view in optical and infrared, and the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) survey, which collects optical, infrared, and ultraviolet observations.

From this data, they identified an additional 283 galaxies at the same distance, along the same straight-line configuration. What's more, the new galaxies also showed the same preference for axial orientation along the length of the filament.

Things in space don't tend to come together in such well-defined structures unless there is something influencing them to do so. In this case, a cosmic filament was the obvious leading candidate – and an exciting one, since large-scale structures made of invisible dark matter are not exactly easy to see or define.

Things got even more interesting when the researchers looked into the galaxies' redshift. On one side of the filament, the light from the galaxies was shifted towards the bluer side of the electromagnetic spectrum, consistent with light wavelengths becoming compressed as the source moves towards the viewer.

The galaxies on the opposite side had light lengthened towards the redder side, which happens when the source is moving away.

This is a clear signal that the entire structure is rotating. The researchers could even model the velocity – about 110 kilometers (68 miles) per second, the same speed at which the Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies are zooming towards each other.

The behavior neatly matches predictions about Tidal Torque Theory, a model that proposes asymmetries in the early Universe's gravitational field transferred angular momentum to forming filaments of the cosmic web – giving them a good spin.

Meanwhile, the presence of diffuse, cold neutral hydrogen gas in the filament and the rich hydrogen content of the galaxies suggests that such filaments can feed galaxies the fuel they need to grow and form stars.

In addition, the alignment of galaxies along the filament suggests that cosmic web filaments can transfer angular momentum to galaxies – a finding that may help fill in the picture of how galaxies get their spin to start with.

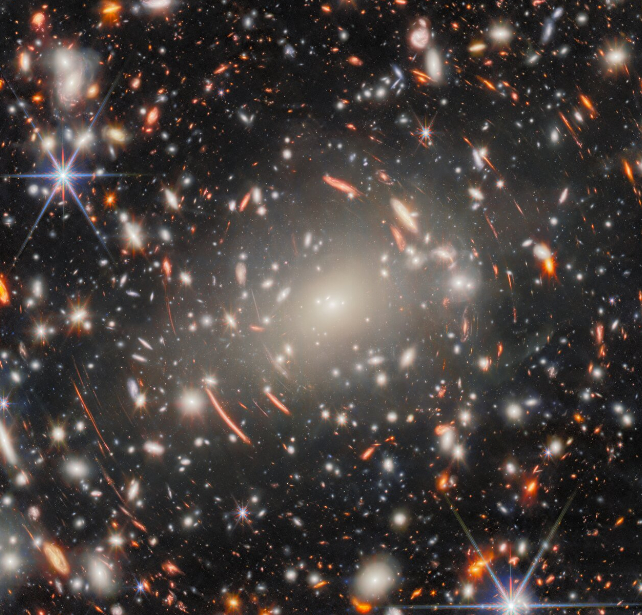

If you look at a deep-field image of the Universe, the galaxies appear to be relatively randomly scattered and unconnected. The detection of this giant filament shows that not only is everything more connected than it seems, but vast, unseen structures may wield a powerful influence that appears invisible until we look more closely.

"We find that the galaxies exhibit strong evidence for rotation around the spine of the filament – making this the longest spinning structure thus far discovered," the researchers write in their paper.

"This structure can prove to be the ideal environment to … pin down the relationship between the low-density gas in the cosmic web and how the galaxies that lie within it grow using its material."

The research has been published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.