If you're an athlete who's suffered one too many knocks to the skull, you'll only get a diagnosis of the degenerative and devastating neurological condition Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) when it's too late to act.

That could change with the discovery of a biomarker specific to the disease, making it possible for physicians to deliver treatments sooner and researchers to track progress more accurately.

Researchers from Boston University and the VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) have identified a protein called CCL11 that not only highlights the presence of CTE, but could be used to distinguish it from other neurodegenerative conditions, such as Alzheimer's disease.

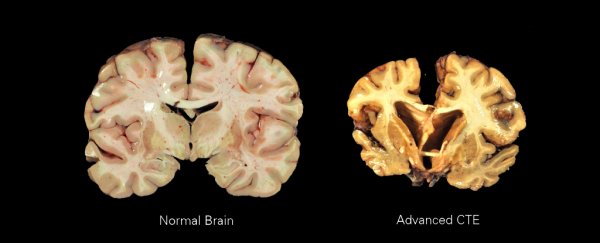

CTE develops as a result of repeated head trauma, the kind footballers and boxers suffer when inertia forces brain to slam into bone inside the skull… over and over again.

Once described as being "punch drunk", the condition is now understood to be the result of clumping tau proteins killing brain cells, not unlike the process behind Alzheimer's disease.

Damage done early in a sporting career might not start to produce symptoms for decades, and even then appear initially as subtle changes in mood or impulse control.

Since CTE eventually progresses into cognitive decline and memory loss, impaired judgement, and dementia, it's important to get in early with well targeted treatments.

The fact that a solid diagnosis is only made by looking closely at the brain post-mortem means this is easier said than done.

Having an easily extracted biomarker of some sort could help spot signs of degeneration while the person is still alive, hopefully long before any symptoms appear.

The protein CCL11 – also known as eotaxin-1 – looks promising as that perfect early indicator.

The protein itself isn't a new discovery, having already been identified as a chemical lure for white blood cells in cases of allergic inflammation, asthma, and inflammatory bowel disease.

It has also been found to increase in the blood and spinal fluid with age.

The researchers identified significant increases in the levels of CCL11 in the brains and spinal fluid samples of deceased individuals who had been diagnosed with CTE post-mortem.

The team analysed fluid and tissue samples taken from 23 football players, 50 individuals with a diagnoses of Alzheimer's, and 18 non-athlete control subjects.

Levels of CCL11 were higher in the football players, increasing with each year of their sporting career.

Because the subjects' spinal fluid showed similar elevated levels of the protein as the tissues taken from the subjects' dorsolateral frontal cortex, it might be possible to look for CTE in living patients without an invasive procedure.

The procedure could also distinguish between CTE and Alzheimer's, which have similar signs of neurodegeneration but could require different treatments.

"This is a step forward from our knowledge gained in understanding CTE from brain donations," says researcher Ann McKee from Boston University and VABHS.

More studies are needed before a reliable diagnostic tool can be developed to predict the stage and severity of the condition's onset.

"What's most likely going to happen is that we'll end up with a panel of biomarkers – maybe three or four – that will let us diagnose CTE reliably," says researcher Jonathan Cherry from Boston University.

Earlier this year, researchers from Boston University Medical School's Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy Centre published evidence of CTE in all but one of 111 footballer's brains donated for analysis.

Of course, prevention is better than cure. Improved regulations and safety equipment would go a long way in reducing the prevalence of CTE.

Before we moralise too much on the perils of contact sports, the condition is also far too common among war veterans who suffered multiple head blows in the field, as well as in victims of domestic violence.

Finding such a link is a monumental step forward in helping a range of people who suffer the consequences of low-level, repeated head trauma.

It might be too late for those already diagnosed after their passing, but we do owe them our gratitude.

"The whole point is to understand as much as we can from the individuals who've fallen, so we can apply it to our future veterans and athletes," says McKee.

This research was published in PLOS One.