Astronomers have finally figured out what the clouds of Uranus consist of - and as it turns out, they smell terrible. For the first time, there's been a clear detection of hydrogen sulfide, the gas that gives rotten eggs - and flatulence - their distinctive aroma.

In spite of decades of observations, the composition of Uranus's clouds has been pretty hard to pin down.

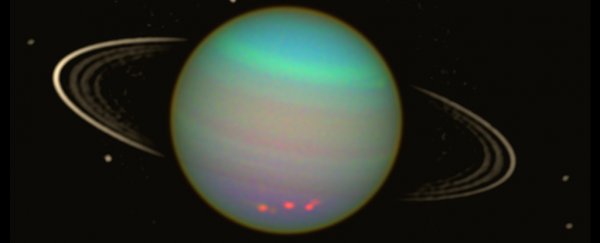

We know there's methane in the atmosphere, because that's what makes the planet such a pretty blue colour (methane is odourless).

We also know there's hydrogen and helium because of observations made by the Voyager 2 probe when it flew past.

But the concentration of other compounds, such as water, ammonia and hydrogen sulfide, has been a bit more difficult to determine, since the planet is so far away and so faint in our telescopes.

And with a cloud deck in particular, often the cloud-forming gas is hidden beneath the region we can see - only a tiny amount lingering above the clouds, extremely difficult to detect.

But equipment and techniques are improving all the time - and an international team of astronomers have found a new way to use the powerful Gemini telescope to peer into Uranus.

Led by planetary physicist Patrick Irwin of the University of Oxford in the UK, the research team used the 8-metre telescope's Near-Infrared Integral Field Spectrometer (NIFS) to perform the most detailed spectroscopic analysis of the clouds to date.

They sampled reflected sunlight from a region just above the visible cloud layer, and sure enough, there was hydrogen sulfide - faint, but unmistakable.

"While the lines we were trying to detect were just barely there, we were able to detect them unambiguously thanks to the sensitivity of NIFS on Gemini, combined with the exquisite conditions on Maunakea," said Irwin.

"Although we knew these lines would be at the edge of detection, I decided to have a crack at looking for them in the Gemini data we had acquired."

The result settles a long-held debate in astronomy: whether hydrogen sulfide or ammonia dominate Uranus's cloud deck.

It also distinguishes Uranus from our Solar System's inner gas planets, Jupiter and Saturn, which have a great deal of ammonia in their atmospheres, but no hydrogen sulfide above the clouds; and could provide clues about Neptune, which is compositionally similar to Uranus, but even farther away.

In turn, this could tell us something about how our Solar System formed in the first place.

"During our Solar System's formation, the balance between nitrogen and sulphur (and hence ammonia and Uranus's newly-detected hydrogen sulfide) was determined by the temperature and location of planet's formation," explained planetary scientist Leigh Fletcher of the University of Leicester.

This means that gas giants Saturn and Jupiter probably formed apart from ice planets Uranus and Neptune - and all of them would have formed apart from the rocky inner planets Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars.

The upcoming generation of both ground- and space-based telescopes, such as the Giant Magellan Telescope and the James Webb Space Telescope, might be able to get a bit more detail.

However, for a really detailed analysis, a space probe would need to be sent to study Uranus. NASA has conducted a study into such a probe, although it wouldn't be launched for at least a few years if the mission is eventually approved.

As for if humans went there? Well, we won't. We're still trying to figure out the logistics of getting to Mars, and Uranus is nearly five times as far. But if we did, the smell of the ammonia and hydrogen sulfide would be the least of our concerns.

Suffocation and exposure in the negative 200 degrees Celsius atmosphere made of mostly hydrogen, helium, and methane would take its toll long before the smell," Irwin said.

The research has been published in the journal Nature Astronomy.