A bolt of lightning that arced across the sky from Texas to Kansas in the fall of 2017 has officially smashed the record for the world's longest.

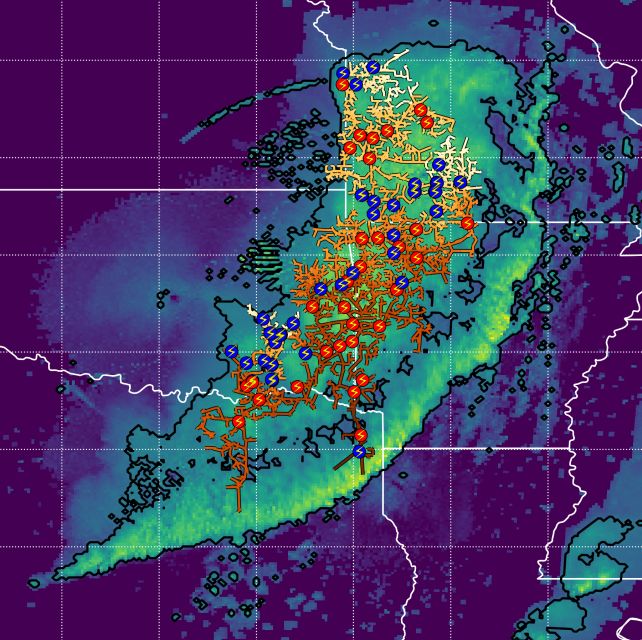

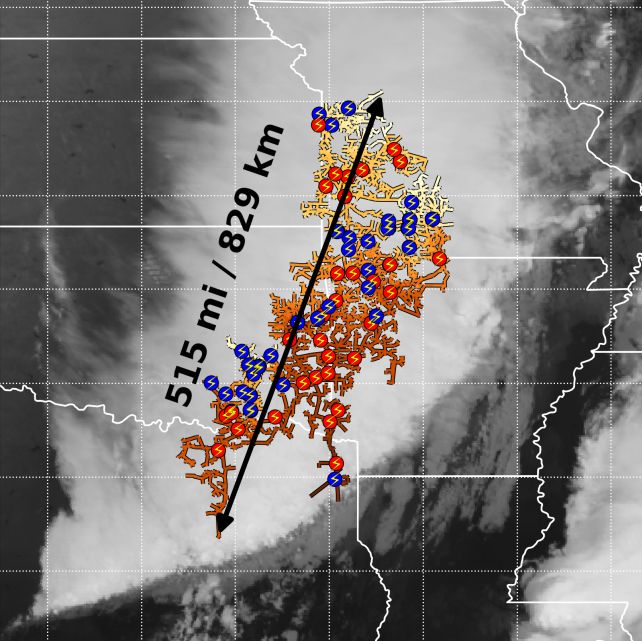

During a major thunderstorm in October 2017, the colossal crack of jagged electricity streaked across the Great Plains of North America for 829 kilometers (515 miles) – a distance that surpassed the previous record by 61 kilometers.

"We call it megaflash lightning and we're just now figuring out the mechanics of how and why it occurs," says geographical scientist Randy Cerveny of Arizona State University and the World Meteorological Organization.

"It is likely that even greater extremes still exist, and that we will be able to observe them as additional high-quality lightning measurements accumulate over time."

Related: Lightning Really Does Strike Twice, And This Is Where It Happens Most

Lightning is one of the most breathtaking phenomena on Earth. It occurs when turbulent conditions in the atmosphere jostle particles around, rubbing them together to generate charge. Eventually, so much charge builds up that it has to go somewhere, producing a discharge of millions of volts across the sky.

The lightning bolt with the previously greatest-known horizontal distance was recorded on 29 April 2020, when a cloud-to-cloud megaflash covered a distance of 768 kilometers across parts of Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi.

Both the previous and current record-holders were detected using the NOAA's GOES-16 and GOES-17 geostationary weather satellites, which are equipped with Geostationary Lightning Mappers (GLMs) that continuously monitor the sky for extreme lightning.

GOES-16 was launched in late 2016, and managed to record the giant storm of October 2017, but the megaflash wasn't detected until a team led by atmospheric scientist Michael Peterson of Georgia Institute of Technology's Severe Storms Research Center revisited the data.

Most lightning bolts are relatively small, less than 10 miles long, and have a tendency to strike vertically. But some travel horizontally through the clouds, and if the cloud complex is particularly large, that can mean giant bolts of lightning. Anything more than 100 kilometers long is considered a megaflash.

Measuring a megaflash is painstaking work that involves putting together satellite and ground-based data to reconstruct the extent of the event in three dimensions. This helps determine that the megaflash is one single lightning strike, as well as measuring just how big it is. Because the strike is often at least partially obscured by cloud, such megaflashes are easy to miss.

The GOES satellites are a major part of the puzzle, since they continuously monitor the sky. They also identified the longest-lasting lightning strike on record back in 2022, a colossal flash that lasted 17.102 seconds during a storm over Uruguay and Argentina in June 2020.

It's no coincidence that both megaflashes occurred over the Great Plains. This region is a major hotspot for the mesoscale convective system thunderstorms that are most conducive to megaflashes. So, if the record is to be broken in the future – which is a strong possibility – it could come from the same region.

"The extremes of what lightning is capable of is difficult to study because it pushes the boundaries of what we can practically observe. Adding continuous measurements from geostationary orbit was a major advance," says Peterson.

"We are now at a point where most of the global megaflash hotspots are covered by a geostationary satellite, and data processing techniques have improved to properly represent flashes in the vast quantity of observational data at all scales.

"Over time, as the data record continues to expand, we will be able to observe even the rarest types of extreme lightning on Earth and investigate the broad impacts of lightning on society," Peterson concludes.

The result has been published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society.