Yawning has an unusual and unexpected effect on the flow of fluid protecting the brain, a recent study reveals, though it's not yet clear what the impact of this shift might be.

According to researchers from the University of New South Wales in Australia, the findings could provide a crucial clue in understanding why humans (and many other species) evolved the capacity to yawn.

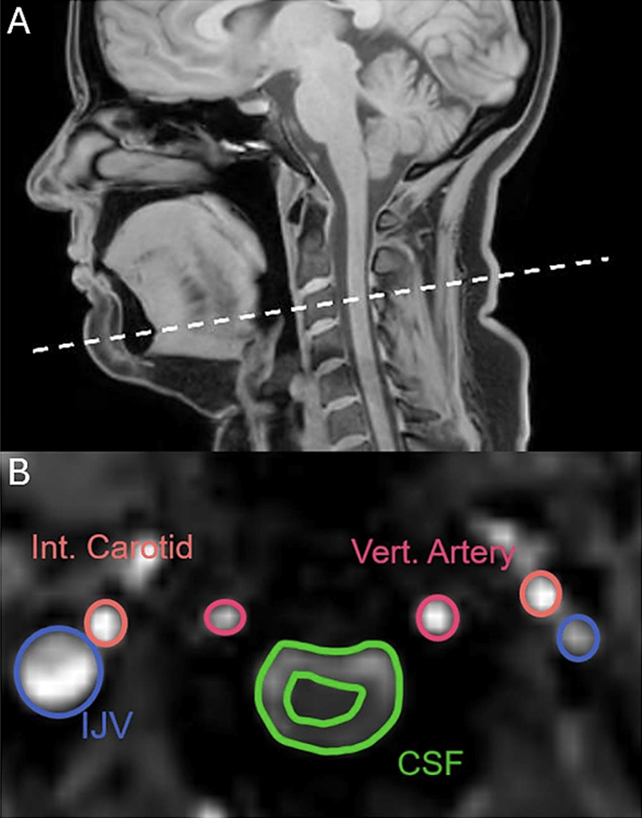

The research team used MRI to scan the heads and necks of 22 healthy participants while they were told to yawn, take deep breaths, stifle yawns, and breathe normally.

Given that yawning and deep breathing share similar mechanisms, the researchers expected them to look similar on the scans. Surprisingly, the images revealed a key difference: unlike deep breaths, yawns sent cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) away from the brain.

"The yawn was triggering a movement of the CSF in the opposite direction than during a deep breath," neuroscientist Adam Martinac told James Woodford at New Scientist.

"And we're just sitting there like, whoa, we definitely didn't expect that."

This wasn't observed in every case, and occurred less often in men, though the researchers caution that this may be due to interference from the scanner itself.

The analysis also revealed that both deep breaths and yawns increased the flow of blood leaving the brain, making more room for fresh blood to be pumped in.

Blood flow didn't change direction with yawns. Yet during its initial stages, carotid arterial blood flow into the brain surges by around a third, providing potential evidence for multiple reasons for the behavior.

In addition, the participants all had unique yawning patterns that were closely followed each time they yawned. It's a sign that we all have our own central pattern generator determining how we yawn.

"This flexibility might account for the variations in inter-participant yawning patterns while still maintaining a recognizable, individual-specific pattern; and implies that the patterns of yawning are not learned but are an innate aspect of neurological programming," write the researchers in their paper.

The next big question is what all of this means, and why yawns should differ from deep breaths so substantially when it comes to CSF, a fluid that keeps the central nervous system running smoothly, delivering nutrients and removing waste.

One possibility raised by the researchers is that yawning has a specific role in cleaning out the brain. Another idea is that it's some kind of brain cooling function in operation.

Yawns do appear to be closely connected to the brain and the central nervous system – bigger brains typically lead to longer yawns, for example, perhaps a nugget of trivia you can share with friends and family the next time you yawn for an extended period of time.

Related: This Article on The Science of Yawning Will Probably Make You Yawn

Yawning continues to be a rather baffling phenomenon with a largely unclear purpose, despite being a behavior seen in many different species, and which tends to be contagious among people and animals.

"Yawning appears to be a highly adaptive behavior and further research into its physiological significance may prove fruitful for understanding central nervous system homeostasis," write the researchers.

The research has yet to be peer-reviewed, but is available on bioRxiv.