For those partnered up in a long-term relationship, studies have shown that different health characteristics can sometimes be shared across the couple – and that extends to psychiatric disorders, according to new research.

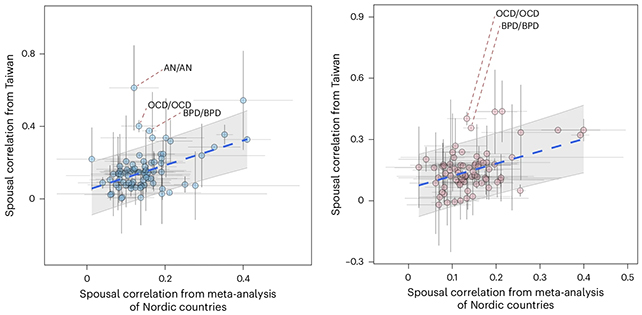

Based on an analysis of more than 6 million couples across Taiwan, Denmark, and Sweden, an international team of researchers found that people were significantly more likely to have the same psychiatric conditions as their partners than would be expected by chance.

Those conditions included schizophrenia, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depression, autism, anxiety, bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), substance abuse, and anorexia nervosa.

Related: Man Hospitalized With Psychiatric Symptoms Following AI Advice

"We found that a majority of psychiatric disorders have consistent spousal correlations across nations and over generations, indicating their importance in the population dynamics of psychiatric disorders," write the researchers in their published paper.

It's a phenomenon the researchers refer to as spousal correlation, and some of the highest correlations have previously been seen in religious beliefs, political views, level of education, and substance use.

The consensus is that there are three factors at play: we typically pick partners like ourselves; our choice of partners is limited by a variety of constraints; and couples spending a long time living together in the same environment tend to become more alike. According to the researchers, all three influences are likely to be involved here, and picking out the most important one is tricky.

Despite the different cultures and healthcare systems in these three countries, the results were statistically similar across the whole dataset, though there were some differences when it came to OCD, bipolar disorder, and anorexia.

"As our results show, spousal resemblance within and between psychiatric disorder pairs is consistent across countries and persistent through generations, indicating a universal phenomenon," write the researchers.

There are some limitations to talk about here: the study didn't distinguish between couples who met before or after their official diagnosis, for example. However, the patterns are strong enough – and across a large enough group of people – to make them meaningful in the study of mental health.

Successive generations were only analyzed in Taiwan, not in the other two countries, and the researchers want to see more data included in future research. A deeper analysis into why this is might be happening is also warranted.

The team also found that having two parents with the same disorder increased the risk of it showing up in children as well. This has important implications for the study of these conditions: genetic analysis studies largely assume that our mating patterns are mostly random, but this research calls that into question.

If people with psychiatric disorders such as the ones studied here are more likely to get together, it adds some important nuance to estimations of how much these disorders are down to genetic risk – further improving our understanding of how they get started, and ultimately, what the best methods of treatment might be.

"Given the ubiquitousness of spousal correlation, it is important to take non-random mating patterns into consideration when designing genetic studies of psychiatric disorders," write the researchers.

The research has been published in Nature Human Behavior.