The small molecule spermine has the potential to stop the toxic build-up of proteins in the brain that characterizes diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's, researchers have found – and it works a bit like melting cheese on spaghetti.

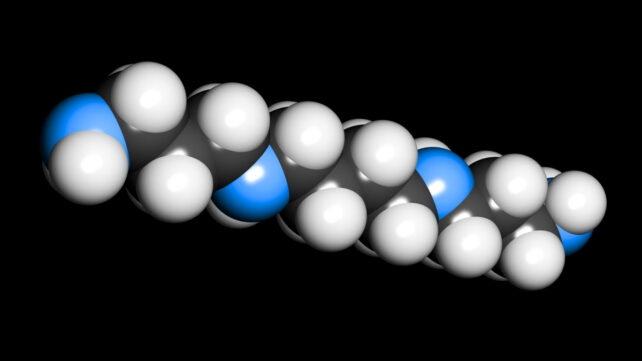

We've known about spermine for more than 150 years: its regular job has to do with the body's metabolism, the business of converting food into energy, and keeping all of the key biological functions running.

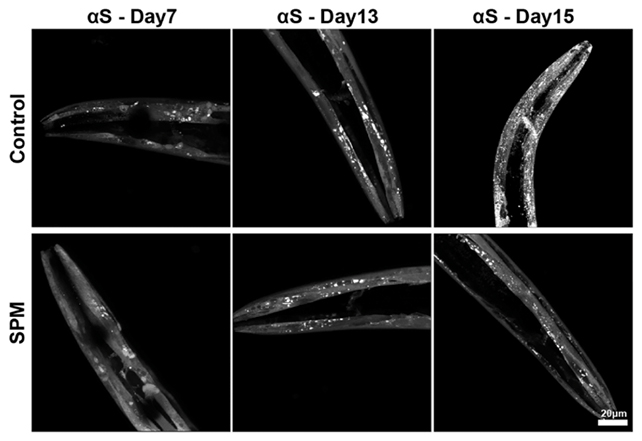

Here, researchers led by a team from the Paul Scherrer Institute (PSI) in Switzerland found that extra spermine given to worms with Alzheimer's and Parkinson's-like symptoms showed improved health in old age, with cells less likely to lose power and wear out.

Related: Switch Turns Brain's Defenses Into Protectors Against Alzheimer's

A close analysis of cells in test tubes showed what was happening: the spermine encourages tau and alpha-synuclein proteins, typically misbehaving in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's, to condense together into liquid-like droplets.

That, in turn, makes these toxic proteins easier for the body's waste recycling system, known as autophagy, to clear out, maintaining normal cell function. There's even a cooking analogy that describes what's going on.

"The spermine is like cheese that connects the long, thin pasta without gluing them together, making them easier to digest," says biophysicist Jinghui Luo, from PSI.

Tau and alpha-synuclein are what's known as amyloid proteins, and when these proteins malfunction, they can form hard, sticky aggregates that go on to damage brain cells in neurodegenerative diseases.

It's not fully clear if these clumps are a cause or consequence of Alzheimer's and Parkinson's, but they're definitely involved.

Spermine creates clumps of a kind, too, but they're softer and more mobile.

This makes them easier to wipe away through the body's clean-up system, while also preventing the proteins from making solid plaques – which then become like crusted food stuck to the bottom of a pan, and much harder to remove.

"Autophagy is more effective at handling larger protein clumps," says Luo. "And spermine is, so to speak, the binding agent that brings the strands together."

"There are only weakly attractive electrical forces between the molecules, and these organize them but do not firmly bind them together."

What's more, the researchers showed that spermine only interferes with tau and alpha-synuclein when they're at too high a concentration, and are more likely to misfold under stress, leading to toxic clumps.

Clearly, it's a long way from test tube and worm experiments to seeing all of this working in a human brain with Alzheimer's or Parkinson's, but these early signs are good ones. Extra spermine might help the brain clear problematic proteins more effectively.

Spermine was chosen for the study because it has previously been shown to protect against damaging processes in the brain.

Related: Speaking Multiple Languages May Slow Brain Aging, Study Suggests

After these results, the researchers are hopeful that spermine and molecules like it could be used to tackle multiple diseases, including cancer – almost like special sauces mixed together to remove toxic processes.

"If we better understand the underlying processes, we can cook tastier and more digestible dishes, so to speak, because then we'll know exactly which spices, in which amounts, make the sauce especially tasty," says Luo.

The research has been published in Nature Communications.