Specific immune cells in the brain may play a crucial role in preventing the onset of Alzheimer's disease, according to a new study – a discovery that could lead to new therapies that try to coax cells into this protective state.

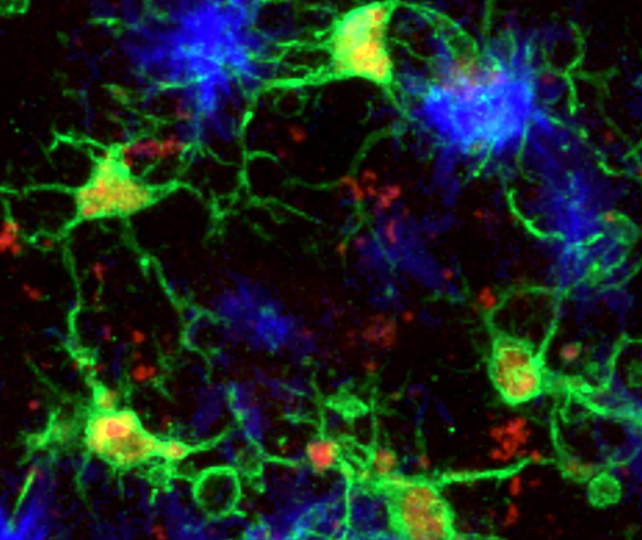

Earlier studies have shown that immune cells in the brain called microglia can effectively tackle the symptoms of Alzheimer's, but also make them worse through inflammation.

Here, an international team of scientists took a detailed look at how microglia switch between those two helpful and harmful modes.

Using mouse models of Alzheimer's, Icahn School of Medicine neuroscientist Pinar Ayata and colleagues found that when microglia get close to the amyloid-beta protein clumps, a tell-tale sign of the disease, they enter a special state of neuroprotection.

Related: Alzheimer's May Not Actually Be a Brain Disease, Reveals Expert

"Microglia are not simply destructive responders in Alzheimer's disease – they can become the brain's protectors," says neuroscientist Anne Schaefer, from the Icahn School of Medicine in New York.

"This finding extends our earlier observations on the remarkable plasticity of microglia states and their important roles in diverse brain functions."

There seem to be two crucial characteristics of this microglia subtype: The cells have lower levels of a protein previously linked to Alzheimer's, called PU.1, and a greater expression of a protein called CD28, a crucial participant in the wider immune system.

Microglia with this combination were better able to slow down the build-up of amyloid-beta protein clumps in mouse brains, while also limiting aggregations of tau – another potentially toxic protein associated with Alzheimer's.

The researchers also stopped CD28 production in mice, finding that harmful, inflammation-causing microglia became more abundant, and that amyloid-beta plaques became more common.

This all fits with earlier studies that have found the onset of Alzheimer's tends to happen later in life among individuals with a genetic disposition towards lower PU.1 expression in specific cells, compared to the general average.

"These results provide a mechanistic explanation for why lower PU.1 levels are linked to reduced Alzheimer's disease risk," says geneticist Alison Goate, from the Icahn School of Medicine.

This seems to be a natural defense against Alzheimer's in the brain, but one which clearly isn't powerful enough to fully stop the disease from progressing.

The researchers are hopeful that future therapies might be able to increase the levels of this microglia subtype – though we need to make sure microglia work the same way in humans first.

Alzheimer's is an incredibly complex disease, involving a host of risk factors, and so an effective treatment will probably need to take aim at several targets at once. One mechanism researchers might consider for future studies is converting microglia into this neuroprotective mode.

The research also adds to our understanding of how Alzheimer's fits in with the immune system as a whole. The modified microglia identified in this study, in mouse brains, act in a similar way to T cells that roam around the rest of the nervous system.

"This discovery comes at a time when regulatory T cells have achieved major recognition as master regulators of immunity, highlighting a shared logic of immune regulation across cell types," says epigeneticist Alexander Tarakhovsky, from the Rockefeller University in the US.

"It also paves the way for immunotherapeutic strategies for Alzheimer's disease."

The research has been published in Nature.