Precise changes in the connectivity between neurons caused by an imbalance of gut bacteria may help explain depressive symptoms in bipolar disorder, a new animal study suggests.

Researchers from Zhejiang University in China used fecal transplants to transfer gut bacteria from people with bipolar disorder into mice. The volunteers had all been diagnosed as being in a depressive phase of bipolar within the last 24 hours.

Through a combination of brain imaging, genetic sequencing, and behavioral tests, the scientists determined that the mice began to exhibit signs of depression – moving less and showing less interest in treats, for example.

Related: Bipolar Disorder Linked to a Higher Risk of Early Death Than Smoking

What's more, crucial measures of brain connectivity weakened. In the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) part of the brain, where a lot of decision making and emotional regulation happens, there were fewer connections (synapses) between cells, and the brain's reward center was effectively cut off.

"Mice transplanted with fecal microbiota from bipolar disorder patients displayed bipolar disorder depression-like behavior, accompanied by changes in neural structure and synaptic connectivity in the mPFC," the researchers write in their published paper.

Animals that received fecal transplants from healthy volunteers showed no such changes.

To test the nature of the depression, the researchers used two different medications: fluoxetine, which is commonly used to treat major depressive disorder, and lithium, a first-line therapy used to stabilize moods in conditions such as bipolar disorder.

No improvement in mood was seen following fluoxetine, yet treatment with lithium resulted in a significant change in behavior.

This matches the treatment response seen in the depressive phases of bipolar disorder, as opposed to depression more generally. It's another sign that the gut bacteria switch had effectively brought bipolar depression along with it.

"Lithium has been reported to regulate the dopamine system and dopamine neuron firing, which are critical for reward processing," write the researchers.

A further analysis of the gut bacteria transplanted from people with bipolar disorder into mice revealed varieties associated with negative health impacts – including Klebsiella (already linked to mood disorders) and Alistipes (linked to depression).

"While specific bacterial genera were identified, more evidence is still needed to determine the exact role of [bacteria] in the pathogenesis of bipolar disorder," the researchers note.

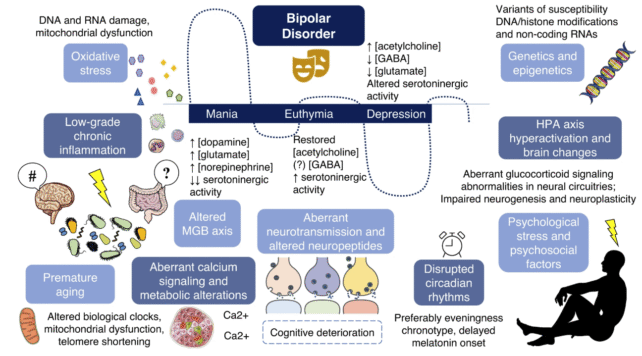

There are several known drivers of bipolar disorder, ranging from genetic to lifestyle and environmental factors, so the researchers aren't suggesting that gut bacteria on their own would trigger the condition.

Gut bacteria could be a contributing factor, layered on top of other components, that possibly makes someone more vulnerable to developing bipolar disorder or worsens their symptoms.

Understanding more about how a particular condition develops and differs from related disorders is a good step towards finding possible treatments.

Imbalances in gut bacteria have been found in people with bipolar disorder, which opens the door to possibly restoring gut bug communities as a way to alleviate symptoms.

Scientists are also making steady progress in identifying how bipolar disorder gets started, pinpointing differences in brain wiring and brain cell activity as possible avenues to explore.

With the condition now affecting around 1 in 50 people worldwide at some point in their lives, there's the potential to improve the lives of millions who experience extreme mood swings.

Related: 'Mini-Brains' Reveal Hidden Signals of Schizophrenia And Bipolar Disorder

"Due to its complex clinical manifestations, the misdiagnosis rate of bipolar disorder is extremely high," write the researchers.

"Therefore, clarifying the pathogenesis of bipolar disorder is of particular importance for early diagnosis and intervention in individuals with bipolar disorder."

The research has been published in Molecular Psychiatry.