An international team of scientists has discovered a record-breaking method of removing a class of harmful 'forever chemicals' from contaminated water.

Their filtration technique can mop up large amounts of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, aka PFAS, about "100 times faster than commercial carbon filters," claims lead author and engineer Youngkun Chung from Rice University in the US.

PFAS are synthetic substances used to protect surfaces from water, fire, and grease. Manufactured since the 1940s, they're used in raincoats, upholstery, non-stick pans, food packaging, firefighting foams, and much more.

Related: 'Forever Chemicals' in US Drinking Water Linked to Cancer, Scientists Find

They certainly proved durable: the carbon-fluorine chain at the core of these molecules is so strong, PFAS are expected to take thousands of years to break down.

Now they're in our water, soil, air, and bodies. That's a problem, because we know at least two of these 'forever chemicals' – PFOA and PFOS – are linked to cancer, cardiovascular disease, fertility issues, and birth defects.

More than 12,000 other variants remain on the market today, with largely unknown health effects.

Governments and industry are making efforts to clean up the mess, but current methods are slow and can create secondary waste.

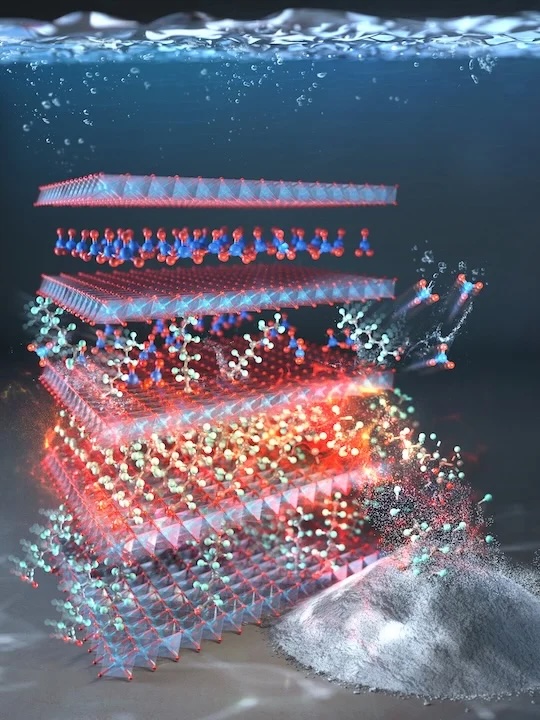

This new filtration method uses a layered double hydroxide (LDH) material that combines copper and aluminum with nitrate.

"This LDH compound captured PFAS more than 1,000 times better than other materials," Chung says. "It also worked incredibly fast, removing large amounts of PFAS within minutes, about 100 times faster than commercial carbon filters."

The material's unique structure emerges from layers of copper and aluminum with a slight imbalance in their charge, sucking in PFOA molecules, which bind tightly with the filter.

Once the adsorption material was saturated with PFOA, the team heated the material and added calcium carbonate, which allowed them to 'clean' the LDH for reuse and strip the PFOA of its fluorine backbone, effectively destroying it.

The remaining fluorine-calcium material can be disposed into landfill safely, Rice engineer Michael Wong told The Guardian.

"We are excited by the potential of this one-of-a-kind LDH-based technology to transform how PFAS-contaminated water sources are treated in the near future," Wong says.

Though it's early days for the technology, it has already shown remarkable promise in lab studies, specifically for PFOA. The filter proved effective in tests with PFAS-contaminated water from rivers, taps, and wastewater treatment plants, and researchers hope one day it can be easily incorporated into drinking water and wastewater treatment facilities.

The research is published in Advanced Materials.