There is more - a lot more - to finding habitable exoplanets than whether they're the right distance from their star for liquid water. Is, for instance, the planet rocky, like Earth, Mars, and Venus? Does it have plate tectonics and a magnetic field? Does it have an atmosphere?

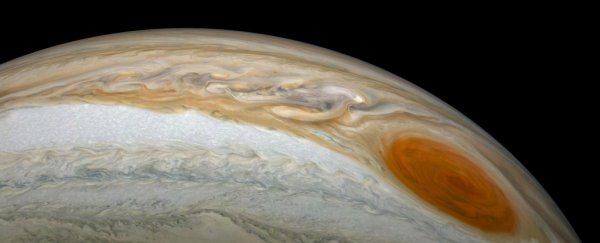

There's also another important question: is the world being adversely affected by any other exoplanets in orbit around the same star? To get a better understanding of this, astronomers are looking at the huge pull the gas giant Jupiter has on the orbit of our own planet.

The technique has been outlined in a new paper accepted into The Astronomical Journal and uploaded to arXiv.

Although the planets in our Solar System are pretty far apart, they are still close enough to affect each other's orbits, just a little.

For Earth, that means interactions with Jupiter and Saturn (primarily) can elongate the elliptical shape of its orbit, and influence its axial tilt, creating glacial and interglacial climate cycles called Milankovitch cycles.

By and large, this hasn't prevented life from thriving, in spite of Ice Age extinction events. But what if Jupiter's influence was stronger and Earth's orbit became even more elongated and eccentric? What would that mean for Earth's habitability?

"If Earth's orbit was as variable as the orbit of Mercury in our solar system, Earth would not be habitable. Life wouldn't be here," astronomer Jonti Horner of the University of Southern Queensland explained to ScienceAlert.

"The eccentricity of Mercury's orbit can get as high as 0.45. If Earth's eccentricity got that high, Earth would be closer to the Sun than Venus when it's closest to the sun, and as far away as Mars when it's at its farthest point."

It was unknown if Jupiter could effect a change of this magnitude, so Horner and an international team of colleagues embarked on a project to find out. They crafted simulations of the Solar System, and moved Jupiter around to see what would happen.

The results were pretty surprising. The team found their simulation worked, meaning they could run a simulation of the system to determine how the planets gravitationally interact, and how the planets actually orbit the star, and map that against our understanding of the Solar System's influence on Milankovitch cycles.

But they also showed how quickly things could fall apart.

"One of the things we found immediately was that it's actually quite easy to make our Solar System unstable," Horner told ScienceAlert.

"In about three quarters of our simulations, as we move Jupiter around, we put it in places where, within 10 million years, the Solar System fell apart. The planets started crashing into each other and being ejected from the Solar System."

While that might sound a little alarming, those results aren't actually relevant to exoplanet research, since any exoplanet systems that hang around long enough to be detectable by us are extremely likely to be stable.

In fact, there was actually some good news in our hunt for alien worlds - in the remaining quarter of the simulations that the team ran to completion, well, Earth was actually pretty normal and habitable.

This, the researchers said, contradicts the Rare Earth hypothesis that proposes that the conditions that gave rise to life on Earth are so unique that they will never be replicated anywhere else in the Universe.

"Earth was pretty much bang in the middle. It wasn't fast. It wasn't slow. It wasn't big, it wasn't small. It was just really average," Horner said.

"Which suggests at least for these kinds of orbital influences, orbital perturbations, instead of it being rare Earth, most planets that you find that are on Earth's orbit in systems that we simulated would be equally suitable for life as Earth, if not better from the point of view of the cyclical [climate] oscillations."

These are important observations, because the ultimate aim of the research is to design a test to help narrow down which exoplanets are worthy of future observation.

At some point in the future, our technology is going to be sophisticated enough to detect many smaller, Earth-sized exoplanets in the habitable zone. But with limited telescope time in high demand, we need to identify other first steps we can take to assess whether a particular exoplanet is worth studying further.

One way would be to examine the effect on potential habitability of any other exoplanets in orbit around the same star.

"We're never going to find planetary systems with just one planet in them and nothing else," Horner explained.

And that's where the simulations come into play. They could be used to help determine, not just the dynamics of the system, but the likelihood that the exoplanet in question has remained habitable on long timescales.

There is some time to go before the team's work can be applied on a large scale. Our current instruments aren't powerful enough to detect the exoplanets it concerns. That's set to change in the next 10 years as more advanced telescopes take to the skies.

That also means there's more work to do. The team hopes that their work means that planetary astronomers can hit the ground running with simulations when habitable exoplanet detections start pouring in. This means the simulations will need to be tweaked to see what happens when you move around other Solar System planets, such as Venus, Mars and Saturn.

"That complexity, I think, is what we're going to be digging into," Horner said.

"And then further down the line, we're also going to be looking at linking this work with the climate models that people develop, to see if you can turn this into a fully predictive climate solution."

"In other words, if you know the orbits of the planets, can you predict how variable the climate is going to be rather than just predicting how variable the the orbit's going to be. It's bringing together climate science and astronomy in quite a brilliant way."

The research has been accepted into The Astronomical Journal, and is available on arXiv.