Carrying too much body fat can have lasting effects on the brain, not to mention other organs. A new study shows that the risk of declining brain health may relate to where on the body fat is stored.

Researchers from Xuzhou Medical University in China looked at MRI scans of 25,997 individuals in a UK health database, with an average age of 55.

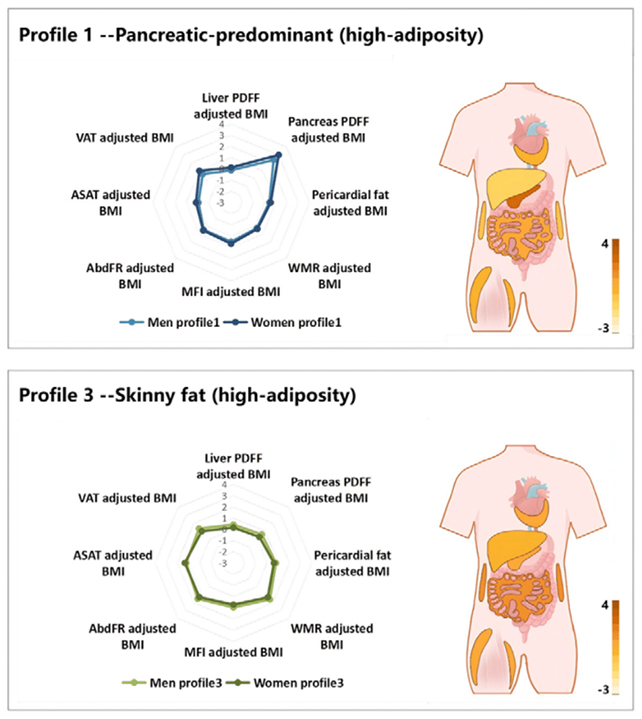

Using a statistical method called latent profile analysis (LPA), the team sorted participants into six groups based on patterns of body fat distribution, then compared their brain scans and cognitive test results.

Compared with the leanest individuals, all five groups with varying distributions of body fat had lower brain volumes and less gray matter, even those who had less body fat than the average person.

"Our work leveraged MRI's ability to quantify fat in various body compartments, especially internal organs, to create a classification system that's data-driven instead of subjective," says radiologist Kai Liu, of the Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University.

"The data-driven classification unexpectedly discovered two previously undefined fat distribution types that deserve greater attention."

The researchers termed these distribution types "pancreatic-predominant" (higher than normal levels of fat around the pancreas) and "skinny-fat" (dense areas of fat around certain organs, despite a fairly average BMI).

Both of these profiles were linked with the highest risk of gray matter decline, white matter lesions, accelerated brain aging, and cognitive decline. They also showed an increased risk of neurological disease (a broad category including conditions such as anxiety, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis and stroke), though there were some differences between the sexes.

The association with brain aging acceleration was most clearly seen in men, while the higher risk of epilepsy (caused by disruptions in the brain's electrical activity) was predominantly linked to the pancreatic-predominant profile in women.

While the study also confirmed that a higher BMI often goes together with more noticeable brain decline, the research adds to a growing pile of evidence that BMI is a rather crude measure of obesity that would benefit from some additional context.

"The detrimental effects of elevated BMI on brain structure have been well documented in previous studies," write the researchers in their published paper.

"Our LPA-derived fat distribution profiles both corroborate this relationship and further reveal that fat distribution patterns may serve as independent neurodegenerative risk factors."

It's important to bear in mind that the associations observed in this study are based on a single snapshot; fat distribution and brain health weren't measured over time, and we can't assume a direct cause-and-effect relationship here.

Related: A Brain Parasite Infecting Millions Is Far Less Sleepy Than We Thought

There were also some limitations in the participants studied, who skewed towards middle age and were all from the UK. Future research into these associations could look at larger, more diverse groups of people.

Even with those caveats, the study adds an interesting extra layer of knowledge about fat and brain health. Potentially, the more scientists understand about this relationship, the better treatments and interventions can become.

If, for example, the profiles identified in this study are validated in subsequent ones, people could get advance warning that they're at higher risk of cognitive decline – giving them the chance to make changes to their lifestyle or medication sooner.

"Brain health is not just a matter of how much fat you have, but also where it goes," says Liu.

The research has been published in Radiology.