'Switches' in our DNA that affect gene activity in cells could be crucial to understanding and possibly treating Alzheimer's disease, with researchers identifying more than 150 control signals in specialized brain cells called astrocytes.

Astrocytes provide essential support to a type of neuron that typically becomes damaged in Alzheimer's. These assistant cells have previously been linked to the disease, with research finding that astrocytes can not only stop being helpful but also become harmful.

This new research, led by a team from the University of New South Wales (UNSW) in Australia, could provide deeper insights into the reasons astrocytes fail and allow Alzheimer's to take hold – and potentially, how to carry out repairs.

Related: Promising New Drug Reverses Mental Decline in Mice With Advanced Alzheimer's

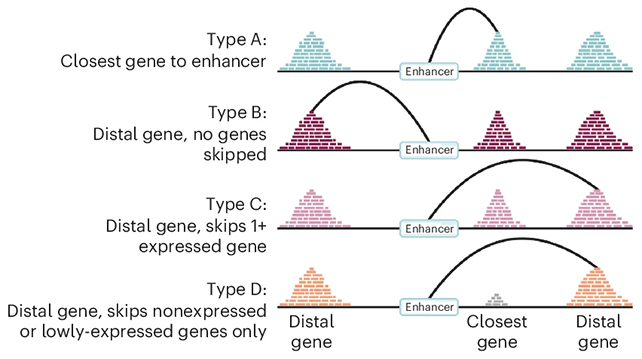

The new findings involve sequences called enhancers (switches that increase gene expression) and regulatory interactions (the signals between enhancers and the genes they control).

Enhancers are located in the non-coding or so-called junk section of our DNA: there are no actual genes here, but there are lots of biological dials and levers that control genes.

"When researchers look for genetic changes that explain diseases like hypertension, diabetes – and also psychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer's disease – we often end up with changes not within genes so much, but in-between," says UNSW molecular biologist Irina Voineagu.

The researchers used a genetic tool called CRISPRi that can mute DNA sections without permanently cutting them. The tool was put to work on astrocytes grown in the lab, testing the functionality of almost a thousand DNA regions thought to harbor enhancers.

Enhancers are often situated far from the genes they control, making them difficult to study and catalog – so being able to get direct evidence of connectivity and signaling across the genome is significant.

"We used CRISPRi to turn off potential enhancers in the astrocytes to see whether it changed gene expression," says molecular geneticist Nicole Green, from UNSW. "And if it did, then we knew we'd found a functional enhancer and could then figure out which gene – or genes – it controls."

"That's what happened for about 150 of the potential enhancers we tested. And strikingly, a large fraction of these functional enhancers controlled genes implicated in Alzheimer's disease."

With potential sequences identified, AI systems may now be trained to spot more enhancers. In the future, these DNA wiring maps should be easier to put together more quickly.

"We're not talking about therapies yet, but you can't develop them unless you first understand the wiring diagram. That's what this gives us – a deeper view into the circuitry of gene control in astrocytes," says Voineagu.

It's important to note that the enhancers identified here are specific to astrocytes, and more experiments are needed to figure out if these enhancers work in the same way when astrocytes become overactive, as they do in Alzheimer's.

Alzheimer's is incredibly complex, and astrocytes that go haywire – and the genes that regulate them – are just part of a much bigger picture. However, this study represents another big step forward in understanding the genes involved and how they might be tweaked to protect against Alzheimer's disease.

The research has been published in Nature Neuroscience.