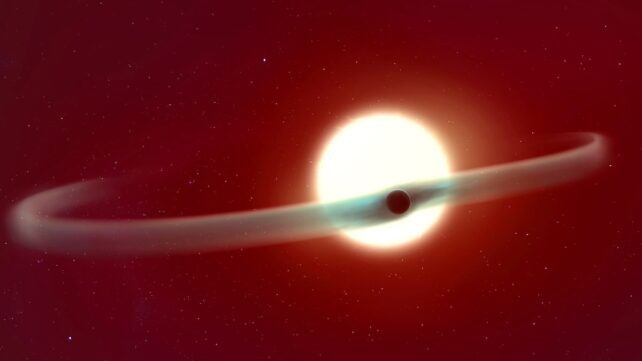

About 880 light-years from Earth, a hot mess of an exoplanet is slowly spilling its atmosphere into space, creating two enormous tails of helium that stretch more than halfway around its star.

This is the first time such a spectacle has ever been observed, according to the authors of a new study. Astronomers have seen exoplanets with leaky atmospheres before, but usually just in fleeting glimpses as the planets transit in front of their host stars.

This time, however, researchers managed to continuously monitor an exoplanet's atmospheric escape throughout its full orbit, shedding new light on the phenomenon – including clues about how it works, what happens to the lost gas, and what it can mean for planetary evolution.

Related: Planet's Record-Smashing Iron Wind Hides a Climate Unlike Anything We've Seen

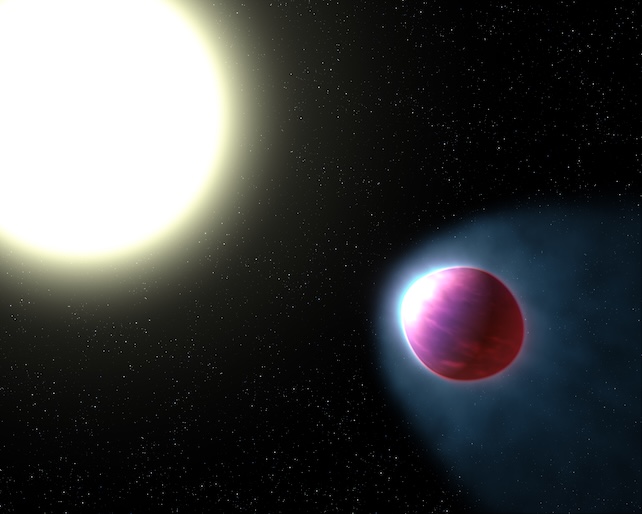

Their study focuses on WASP-121b, also known as Tylos, an extreme exoplanet already famous for quirks such as clouds of vaporized metal, rains of rubies and sapphires, and the fastest atmospheric jet stream known to science.

It's an ultra-hot Jupiter; a category of extrasolar gas giants generally similar to Jupiter, except much closer to their host stars and therefore much hotter.

Tylos is so close to its star, in fact, it needs only 30 hours to complete an orbit – meaning a year on Tylos is about as long as one day on Earth.

That's a bit close to its parent star for comfort. Intense radiation heats the planet's atmosphere to thousands of degrees, creating extreme conditions that enable many oddities, including the escape of lighter gases like hydrogen and helium into space.

Atmospheric escape can happen quickly in some contexts, but it's often a gradual process, with small amounts of gases trickling away. Nonetheless, even a slow leak could significantly change a planet's size and composition over time, and possibly influence its evolution.

Most of what we know about atmospheric escape comes from data collected during planetary transits, which may last just a few hours. This approach captures only a sliver of what's happening throughout an exoplanet's orbit.

In the new study, researchers observed Tylos for nearly 37 hours straight using the JWST's Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph, yielding unprecedented data from more than one full orbit.

They scanned Tylos' path for helium absorption at infrared wavelengths, an established signal of atmospheric escape. Its helium haze was found to extend far beyond the planet itself, occupying almost 60 percent of the planet's orbit.

That's the longest continuous observation of atmospheric escape to date, and it reveals "a persistent and large-scale outflow," the researchers write.

Strangely, Tylos isn't generating just a single stream. Helium atoms were seen forming two distinct tails, one trailing behind the planet and another reaching ahead of it. Both tails are enormous, together covering an area more than 100 times the diameter of Tylos.

"We were incredibly surprised to see how long the helium outflow lasted," says lead author Romain Allart, an astronomer with the Trottier Institute for Research on Exoplanets and the Université de Montréal.

"This discovery reveals the complex physical processes sculpting exoplanet atmospheres and how they interact with their stellar environment," Allart adds. "We are only starting to uncover the true complexity of these worlds."

The presence of two helium tails poses a puzzle for astronomers. Existing computer models can explain a single tail of gases leaking from a planet, but they struggle to reconstruct the origin of double tails stretching in different directions.

Radiation and the stellar wind may direct one tail to trail behind the planet, the researchers suggest, while the star's gravity may pull in the leading tail, causing the stream to curve ahead of Tylos in orbit.

More research is needed to investigate how these and other forces influence atmospheric outflows, and to inform new 3D simulations that more accurately model the physics involved.

More research is needed to investigate how these and other forces influence atmospheric outflows, and to inform new 3D simulations that more accurately model the physics involved.

Aside from explaining Tylos' twin helium tails, a deeper understanding of atmospheric loss could reveal broader secrets about planetary evolution – including whether such gas leaks can transform massive gas giants into smaller, Neptune-like planets or even into stripped-down, rocky cores.

"This is truly a turning point," Allart says. "We now have to rethink how we simulate atmospheric mass loss – not just as a simple flow, but with a 3D geometry interacting with its star. This is critical to understand how planets evolve and if gas giant planets can turn into bare rocks."

The study was published in Nature Communications.