When it finally launches, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) will give us our best look yet at the Universe around us – it's the largest and most powerful telescope humans have ever built, and a new preprint study says it could spot potential signs of alien life in as little as 20 hours of transit time.

In advance of its expected launch in late December, one researcher has been looking into the potential of the JWST in terms of the transmission spectroscopy it could carry out – a promising method for detecting the composition of a planet's atmosphere by the way that light from a neighboring star passes through it.

Using the example of TRAPPIST-1e – an exoplanet we know to be a promising candidate for biosignatures, or signs of alien life – astronomer Thomas Mikal-Evans has worked out how long it might take the JWST to detect methane (CH4) and carbon dioxide (CO2) in the planet's atmosphere. He's made the results available on the preprint server arXiv ahead of peer review.

Depending on numerous variables, including the level of cloud and haze, a combination of CH4 and CO2 might be found in as little as five transits – brightness readings carried out by the telescope. At 4.3 hours per transit, that's a little over 20 hours in total.

"If TRAPPIST-1e has an atmospheric composition similar to that of the Archean Earth, strong detections for both CH4 and CO2 are possible for 5-10 transit observations under the assumption of well-behaved instrumental noise and neglecting the effect of stellar variability," writes Mikal-Evans, from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Germany.

Of course, the presence of CH4 and CO2 around TRAPPIST-1e wouldn't be the smoking gun of alien presence, but it's the sort of evidence astronomers hunt for when searching the skies for biosignatures.

Bear in mind that the 20-hour estimate is right at the lower end; Mikal-Evans's data suggest it could also take more than 200 hours to get a proper reading, depending on factors such as how cloudy the atmosphere ends up being. Besides, the exoplanet may end up having an altogether different atmospheric composition.

However, the result is still an exciting one. "It is widely anticipated that JWST will be transformative for exoplanet studies," Mikal-Evans writes, and his results demonstrate that not only will it be possible to use the telescope to hunt for biosignatures in the atmospheres of distant alien planets, but it could even be achieved with relative ease.

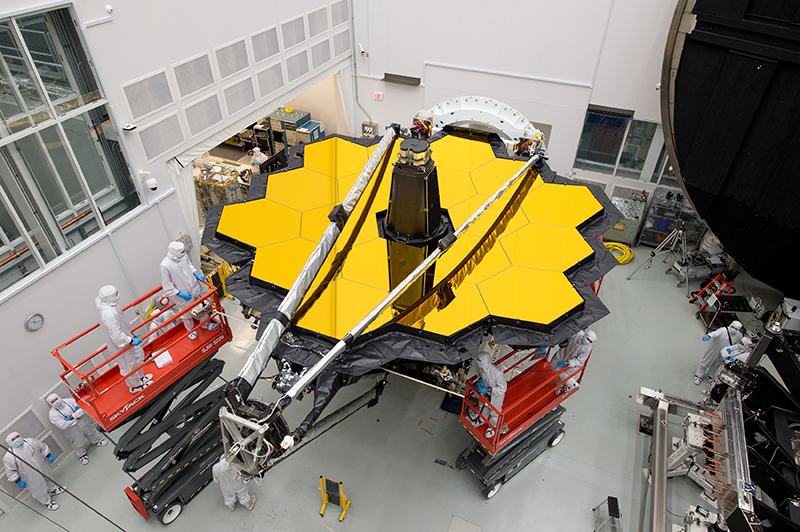

(NASA/Desiree Stover)

(NASA/Desiree Stover)

Named after James E. Webb, a NASA administrator between 1961 and 1968 and a key figure in the Apollo space program, the JWST is a joint venture between NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA), and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA).

The space agencies behind the JWST are concentrating on getting it actually into orbit first of all. In the last few days, unexpected vibrations due to an untimely clamp band release have delayed the launch of the telescope by a few more days while all the instruments get rechecked. It's still hoped that blast off can happen on December 22.

However, this isn't the first time the telescope has been pushed back. In fact, the project was first envisioned in the 20th century, and the telescope was originally going to launch all the way back in 2007.

Since then, countless delays, costing issues, and technical challenges have got in the way (including the latest issue of a global pandemic). The telescope is currently being prepared at a base in Kourou in French Guiana.

When the JWST does get up into space, expect a long series of exciting discoveries: the telescope is fitted with instruments that enable it to see across longer distances and longer wavelengths, revealing signs of the early Universe that its predecessor Hubble can't spot. At its center is a huge golden mirror designed to help focus light.

Hopefully, by the end of the year, the JWST should have left Earth – and we're very much looking forward to what it finds first.

The preprint on the biosignature study is available on arXiv.