There's a lot of evidence that more exercise helps reduce cancer risk – but why are the two connected?

According to a new mouse study, it may be down to a metabolic shift that appears to give muscle cells more fuel to burn, while 'starving' cancer cells of energy to grow.

Led by a team from Yale University, the researchers behind the study analyzed the metabolic reactions of mice with breast cancer or melanoma tumors, split into groups based on the animals' diet and exercise levels.

Related: Regular Exercise Reduces Death From Colon Cancer by 37%, Study Finds

The team used molecular tracers to ascertain where glucose was metabolised in the mice, and found that the active animals were effectively rerouting energy and fuel away from the cancer cells to the muscles.

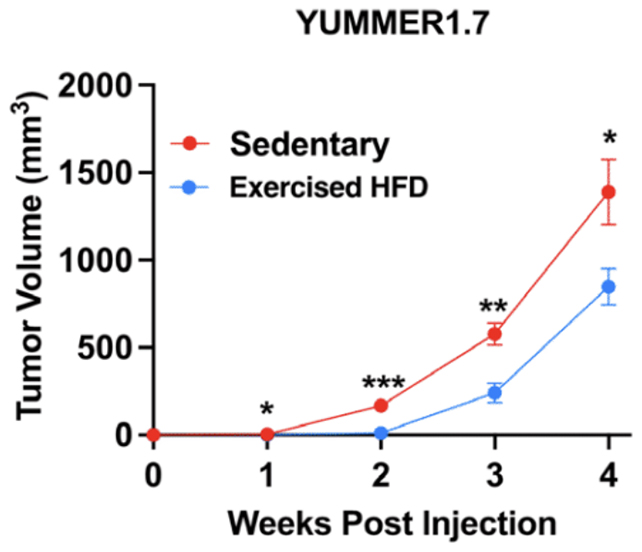

After four weeks, the mice on a high-fat diet that exercised regularly had significantly smaller tumors than animals on the same diet that hadn't been active.

"Obese mice which underwent four weeks of voluntary wheel running after tumor injection exhibited nearly a 60 percent reduction in tumor size," Yale University physician-scientist Brooks Leitner and colleagues report in their published paper.

The team also identified 417 different metabolism-related genes that were expressed differently in active mice compared to sedentary, yet lean mice.

Taken together, these molecular changes showed the tumors had entered a high-stress survival mode.

Exercise especially dialed down a protein called mTOR in the animals' tumors, which could be significant in restricting their growth; a finding that could inform searches for new treatments.

Related: One Critical Factor Predicts Longevity Better Than Diet or Exercise, Study Says

According to the researchers, the findings suggest glucose is "a key metabolic mediator of the tumor-suppressive effects of exercise".

However, they also note that "this metabolic relationship and the ability for exercise to slow tumor growth may depend on exercise duration."

Cancer in all its various forms is a complex disease, with multiple mechanisms involved in the growth and establishment of tumors. Patients won't ward off cancer with trips to the gym alone.

Related: Sperm Donor With Rare Cancer-Risk Gene Fathers Nearly 200 Children

But physical activity could be a significant factor in maximizing the chances of preventing the disease from emerging. Obese mice that exercised for two weeks before tumors were implanted had smaller tumours than sedentary mice, the researchers also found.

"These data highlight the importance of a nuanced, systemic view of the metabolic effects of exercise in cancer," Leitner and colleagues write.

It's encouraging that the same mechanisms appear to be at play in two types of tumor; it suggests that the benefits of exercise are not limited to a single cancer.

Although scientists still need to see if these same processes are at work in humans to know whether the findings apply to us.

To this end, the researchers are keen to continue their investigation with human cancer tumors, and with more structure around the types and duration of exercise undertaken. That should tell us more about exactly how staying active helps protect against cancer.

"Examination of the role of fitness on the molecular pathways altered by exercise may uncover new therapeutic targets in precision oncology, particularly in patients who cannot tolerate exercise," the researchers conclude.

The research has been published in PNAS.