We've seen black hole mergers. We've seen that incredibly memorable neutron star merger. Now the LIGO-Virgo collaboration seems to be mixing it up, with what could be the first ever gravitational wave detection of a black hole devouring a neutron star.

It's only just come in, a burst of unusual gravitational waves, ripples in the very fabric of spacetime, the shockwaves of some colossal event, detected by the LIGO and Virgo observatories at 15:22:15 UTC on 26 April 2019.

Astronomers are still analysing the event, and it could turn out to be something completely different. But ever since that first gravitational wave discovery announced in February 2016 blew the field wide open, astronomers have been hoping to detect many different kinds of mergers.

An initial analysis put the odds that this event is a black hole-neutron star merger at only 13 percent, but scientists are still hopeful.

"This candidate is different from everything else that we've observed," as LIGO team member Gabriela González at Louisiana State University told New Scientist.

There isn't a huge amount of difference between a black hole and a neutron star. Both are the result of the death of a star. Once a star has burned through its supply of hydrogen, and shed its outer material in a series of explosions, its core collapses under its own weight.

If that core is below about three times the mass of the Sun (with the original star between 10 and 30 times the mass of the Sun), it becomes a neutron star. If it's more than three Solar masses, it becomes a black hole. (Stars that are too small to become neutron stars become white dwarfs. That's where the Sun is headed.)

We know there are binary systems with mass disparities between the two stars. So, it's absolutely possible that there are black hole-neutron star binary systems. But this event would be our first evidence that such binary systems exist.

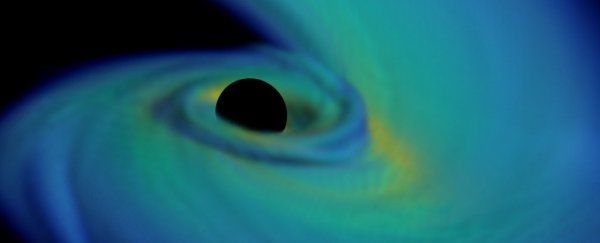

The mechanism is the same as black hole-black hole and neutron star-neutron star mergers. The two objects are locked in a death spiral, orbiting closer and closer until BOOM! the two objects merge.

But there would be some differences. Because the black hole is the far more massive object, it would subsume the neutron star's mass into its own. And, rather than a circular orbit, the neutron star's path around the black hole would be more spherical - making it a much better testbed for the effects of relativity.

The event has been provisionally named S190426c. Based on the signal triangulation capabilities added by the Virgo detector, it seems to have taken place around 1.2 billion light-years away.

Since LIGO was switched back on at the beginning of April after a year of upgrades, it has been making all its detections public. A description of the S190426c event, as well as maps of the that show the region of the sky it came from, have been made available on the GraceDB website, so that astronomers around the world can perform their own follow-up observations.

As the neutron star becomes disrupted and then devoured by the star, it's expected that it will produce a flare of electromagnetic activity. This has not yet been detected, which potentially points to a different kind of merger.

"The fact that we haven't found a counterpart yet would mean that it's farther away, which is more consistent with a neutron star-black hole system," González told New Scientist. "We wouldn't see binary neutron stars that far."

But, since its upgrade, the LIGO-Virgo collaboration has been absolutely killing it - it's detected a number of events, including a second neutron star collision. So even if this event doesn't turn out to be the hotly anticipated black hole-neutron star merger, it seems like detecting one is only a matter of time.

This is the brave new world of gravitational wave astronomy, and it is glorious.