A construction site dating back nearly 2,000 years to the putative demise of Pompeii in 79 CE has revealed new evidence for the secret behind Ancient Rome's ultra-durable concrete.

Last year, from under the volcanic ash that buried Pompeii, archaeologists uncovered a fully intact construction site – a rare snapshot of Roman building work frozen in time.

That site includes neatly organized piles of materials, including the ingredients used to mix the famously durable concrete behind monuments such as the Pantheon, whose vast unreinforced dome has stood for millennia.

Related: You Won't Believe What Scientists Found in an Ancient Roman Ruin

A brand new analysis reveals that the secret is a technique that materials scientist Admir Masic of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) calls "hot-mixing".

It involves directly blending the concrete's ingredients: a volcanic ash mix called pozzolan, together with quicklime, which reacts with water to generate intense heat inside the mixture.

"The benefits of hot mixing are twofold," Masic said back in 2023 when he first discovered the technique through experimentation.

"First, when the overall concrete is heated to high temperatures, it allows chemistries that are not possible if you only used slaked lime, producing high-temperature-associated compounds that would not otherwise form. Second, this increased temperature significantly reduces curing and setting times since all the reactions are accelerated, allowing for much faster construction."

A third, and crucial, benefit is that the surviving chunks, or clasts, of lime give the concrete a remarkable self-healing ability. This could be a major reason ancient Roman monuments still stand while other civilizations have crumbled.

When cracks form in the concrete, they preferentially propagate toward the lime clasts, which have a higher surface area than other matrix particles. When water enters the crack, it reacts with the lime to form a calcium-rich solution that dries and hardens as calcium carbonate, gluing the crack back together and preventing it from spreading further.

"There is the historic importance of this material, and then there is the scientific and technological importance of understanding it," Masic says.

"This material can heal itself over thousands of years, it is reactive, and it is highly dynamic. It has survived earthquakes and volcanoes. It has endured under the sea and survived degradation from the elements."

Although the hot-mixing technique offered solutions to the puzzles posed by Roman concrete, it raised a new one: The recipe did not match the description of how to make the building material in the 1 BCE treatise De architectura by architect Vitruvius.

The Vitruvian method involved first mixing the lime with water in a process known as slaking, before mixing the slaked lime with the pozzolan. However, this process does not produce the lime clasts observed in real Roman concrete samples.

Related: Scientists Developed a Kind of 'Living Concrete' That Heals Its Own Cracks

This mismatch has long puzzled scientists. Vitruvius' writings represent the most complete surviving documents on Roman architecture and construction. He describes a technique called opus caementicium for building walls, but physical samples from ancient buildings contradicted his instructions.

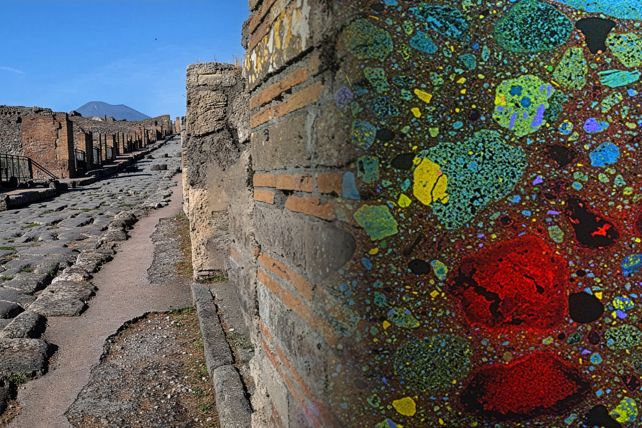

The Pompeii materials put the mystery to bed. Masic and his team used isotope analysis on five of the dry piles of materials, identifying pozzolan made of pumice and lithic ash, quicklime, and even lime clasts.

Most tellingly, these dry ingredients were premixed – an archaeological smoking gun.

Under the microscope, the mortar samples from the walls revealed unmistakable signatures of hot mixing: fractured lime clasts, calcium-rich reaction rims that grew into volcanic ash particles, and tiny crystals of calcite and aragonite forming within pumice vesicles.

Raman spectroscopy confirmed the mineral transformations, while isotope analysis showed the chemical pathways of carbonation over time.

"Through these stable isotope studies, we could follow these critical carbonation reactions over time, allowing us to distinguish hot-mixed lime from the slaked lime originally described by Vitruvius," Masic says.

"These results revealed that the Romans prepared their binding material by taking calcined limestone (quicklime), grinding [it] to a certain size, mixing it dry with volcanic ash, and then eventually adding water to create a cementing matrix."

This doesn't necessarily mean Vitruvius was wrong – he may have described an alternative method for making concrete, or his work may have been misinterpreted – but it does indicate that the most durable form of the material had to emerge from the hot-mixing technique.

This, the researchers believe, is information that can be incorporated into the way we make concrete, many centuries after the Roman Empire fell, leaving its monuments standing as a reminder not just of its grandeur but also of the ingenuity of its people.

Modern concrete is one of the world's most widely used building materials. It's also remarkably lacking in durability, often crumbling in decades under environmental stress. Producing it is terrible for the environment, too, requiring a huge resource cost and contributing to greenhouse emissions.

Simply improving the durability of concrete has the potential to make it significantly more sustainable.

Related: Scientists Discovered an Amazing Practical Use For Coffee Ground Waste

"We don't want to completely copy Roman concrete today. We just want to translate a few sentences from this book of knowledge into our modern construction practices," says Masic, who has started a company called DMAT to do just that.

"The way these pores in volcanic ingredients can be filled through recrystallization is a dream process we want to translate into our modern materials. We want materials that regenerate themselves."

The research has been published in Nature Communications.