When Nebraska woman Alex Simpson was just two months old, she was diagnosed with a rare congenital brain condition that meant she may not survive to her first birthday.

But despite medical odds, she and her family just celebrated her 20th birthday on November 4 this year.

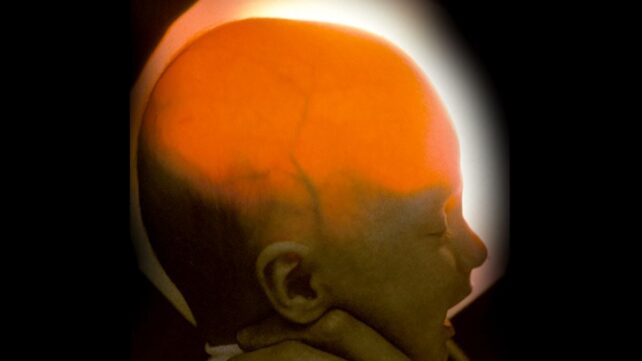

Simpson's condition, hydranencephaly, means her cerebral hemispheres – the two large lobes that typically make up most of the human brain, responsible for cognitive function, voluntary movement, and sensory processing – are almost nonexistent. While her brainstem and some other brain parts remain, the rest of her cranial cavity is filled instead with cerebrospinal fluid.

Hydraencephaly is incurable, and is managed with intensive supportive care.

Related: This Woman Lived 24 Years Without Knowing She Was Missing Her Entire Cerebellum

While babies born with hydranencephaly may seem normal at birth, with a typical head size and reflexes, signs of irritability, increased muscle tone, and symptoms such as seizures and hydrocephalus (a build-up of cerebrospinal fluid in and around the brain) can emerge. This may explain why doctors took two months to detect Simpson's condition.

"Technically, she has about half the size of my pinky finger of her cerebellum in the back part of her brain, but that's all that's there," Alex's father, Shawn Simpson, told Omaha news station KETV earlier this month.

This means Simpson's vision and hearing are impaired, though her cerebellum maintains some awareness of her surroundings. Her family say they nevertheless have a strong relationship with her.

"She knows her mum and her dad, her little brother. She knows when good things are going on around us, she knows when bad things are going on around her," Alex's father said in a KETV interview for Alex's 10th birthday.

Alex's brainstem (which conveys signals between the brain and body) is intact, and so are her meninges (the brain's protective membranes) and basal ganglia, preserving her most vital functions.

The basal ganglia are typically involved in motor movements, learning, cognition and emotion, though it is unclear how the lack of cerebral hemispheres affects these functions.

Hydranencephaly begins in the early stages of fetal development, and most infants with the condition do not survive to birth. It affects about 1 in 10,000 births worldwide, and occurs in fewer than 1 in every 250,000 births in the US.

In most cases, early signs of this condition are detected on ultrasounds when the baby is still in the womb. If the condition is detected in utero, parents may opt for abortion, weighing up the child's quality of life, the emotional and financial impact of the care needed to manage symptoms, and personal beliefs.

We don't know what causes hydranencephaly, but some research suggests it may arise when some form of vascular injury, such as a stroke or infection, blocks blood supply to the brain.

Signs of the condition usually emerge in the second trimester, but can appear as early as 12 weeks in some cases.

"While we are still learning, hydranencephaly is presumed to be a destructive process impacting the brain, commonly due to a variety of causes," pediatric neurologist Sumit Parikh from the Cleveland Clinic told Judy George at MedPage Today.

"Less commonly, genetic disorders impacting cerebral blood vessel formation have been identified," Parikh said. "Considering we have not had comprehensive testing like whole-genome sequencing until relatively recently, it is possible that genetic causes have been underestimated."

Hydranencephaly is different from the similarly named hydrocephalus, in which fluid builds up in an otherwise fully-formed brain. That condition, which can be a symptom of hydranencephaly or occur separately, can also lead to reductions in the cerebral hemispheres due to increased pressure inside the skull.