Our bodies are colonized by a teeming, ever-changing mass of microbes that help power countless biological processes. Now, a new study has identified how these microorganisms get to work shaping the brain before birth.

Researchers at Georgia State University studied newborn mice specifically bred in a germ-free environment to prevent any microbe colonization. Some of these mice were immediately placed with mothers with normal microbiota, which leads to microbes being transferred rapidly.

That gave the study authors a way to pinpoint just how early microbes begin influencing the developing brain. Their focus was on the paraventricular nucleus (PVN), a region of the hypothalamus tied to stress and social behavior, already known to be partly influenced by microbe activity in mice later in life.

Related: An Extra Sense May Connect Gut Bacteria With Our Brain

"At birth, a newborn body is colonized by microbes as it travels through the birth canal," says behavioral neuroscientist Alexandra Castillo Ruiz.

"Birth also coincides with important developmental events that shape the brain. We wanted to further explore how the arrival of these microbes may affect brain development."

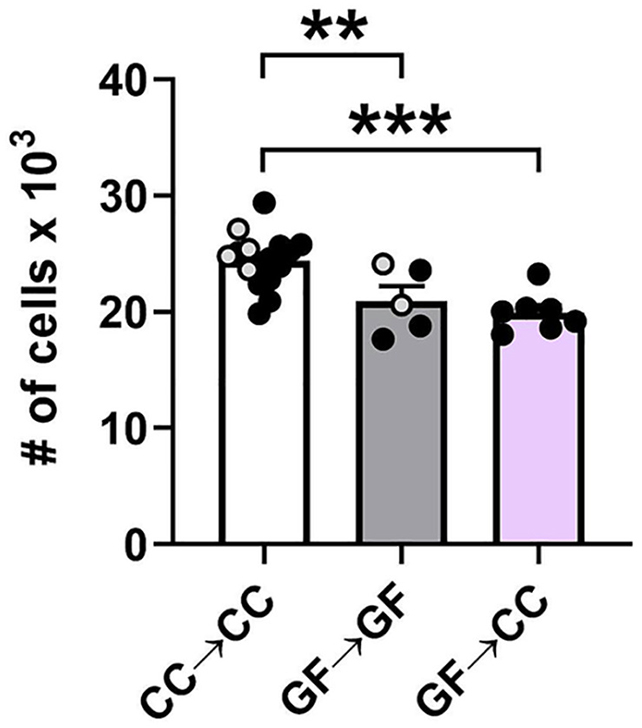

When the germ-free mice were just a handful of days old, the researchers found fewer neurons in their PVN, even when microbes were introduced after birth. That suggests the changes caused by these microorganisms happen in the uterus during development.

These neural modifications last, too: the researchers also found that the PVN was neuron-light even in adult mice, if they'd been raised to be germ-free. However, the cross-fostering experiment was not continued into adulthood (around eight weeks).

The details of this relationship still need to be worked out and researched in greater detail, but the takeaway is that microbes – specifically the mix of microbes in the mother's gut – can play a notable role in the brain development of their offspring.

"Rather than shunning our microbes, we should recognize them as partners in early life development," says Castillo-Ruiz. "They're helping build our brains from the very beginning."

While this has only been shown in mouse models so far, there are enough biological similarities between mice and humans that there's a chance we're also shaped by our mother's microbes before we're born.

One of the reasons this matters is because practices like Cesarean sections and the use of antibiotics around birth are known to disrupt certain types of microbe activity – which may in turn be affecting the health of newborns.

In particular, it could be leading to changes in stress and social behavior, as handled by the PVN part of the brain – though it's too early to make any definitive conclusions. In the words of the researchers, it "merits further investigation".

An obvious follow-up would be to investigate how the microbiota of mothers-to-be can be altered. Previous research has already linked these gut microbes to changes in diet, sleep patterns, alcohol intake, and overall health, for example.

"Our study shows that microbes play an important role in sculpting a brain region that is paramount for body functions and social behavior," says Castillo-Ruiz.

"In addition, our study indicates that microbial effects start in the womb via signaling from maternal microbes."

The research has been published in Hormones and Behavior.