Long-term exposure to the pesticide chlorpyrifos, widely used on US farms, has been linked to a more than 2.5-fold increase in the risk of developing Parkinson's disease, according to new research.

The finding comes from a large community-based case–control study led by scientists at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). The team also used animal models to identify the specific kinds of brain damage that chlorpyrifos might cause.

It adds to existing concerns around pesticides and Parkinson's, although establishing long-term chemical exposure and separating it from other risk factors, such as genetics, can be challenging.

Related: Parkinson's Discovery Suggests We May Have an FDA-Approved Treatment Already

"This study establishes chlorpyrifos as a specific environmental risk factor for Parkinson's disease, not just pesticides as a general class," says neurologist Jeff Bronstein, from UCLA.

The researchers compared 829 people diagnosed with Parkinson's disease with 824 people without the condition. By combining participants' home and workplace addresses with California pesticide-use records dating back to 1974, the team estimated each person's exposure to chlorpyrifos.

Those with the highest workplace exposure for the longest periods had 2.74 times higher odds of developing Parkinson's, compared with people who had minimal or no exposure.

What's more, the risk rose significantly for exposure going back more than a decade, consistent with the development of Parkinson's, which often starts many years before symptoms appear.

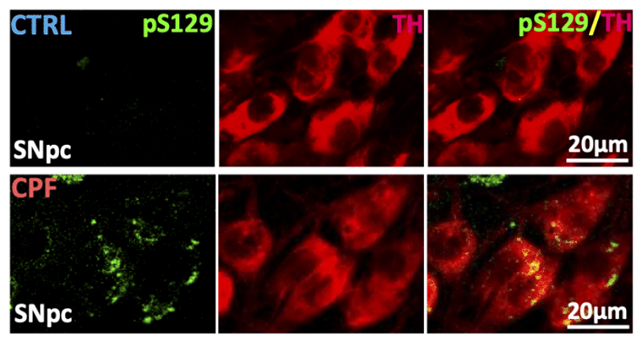

To test whether the association might be causal, the team conducted experiments in mice and zebrafish. Mice exposed to chlorpyrifos showed signs of impaired movement, and lost dopamine-producing neurons in their brain – a hallmark of Parkinson's.

Clumps of the alpha-synuclein protein were also seen in the mouse brains – again matching pathological markers of Parkinson's. In zebrafish, chlorpyrifos interfered with autophagy, a key cellular waste-disposal process. When the researchers stimulated autophagy, neurons were better protected.

That link between chlorpyrifos and autophagy is significant: Several previous studies have shown autophagy may be one of the pathways driving Parkinson's-related brain damage, and it might be the route chlorpyrifos chemicals take, too.

"By showing the biological mechanism in animal models, we've demonstrated that this association is likely causal," says Bronstein.

Chlorpyrifos has already been linked to brain abnormalities in children and is banned in the UK and the European Union. In the US, its use has been somewhat restricted in recent decades, but the pesticide is still applied to food crops in many states.

It looks increasingly likely that chlorpyrifos contributes to Parkinson's risk, but it's only one factor among many. While it's not clear how Parkinson's gets started, we do know that risk factors include the genes we're born with, poor quality sleep, and even how close we live to a golf course (perhaps due to pesticide use).

Related: Mosquitoes Are Feeding on Us More Often – And Scientists Say We're to Blame

In the future, the researchers hope to look at other types of pesticides and their potential effects on the brain. They also want to explore whether treatments that prevent disruption of autophagy could protect against the damage caused by chlorpyrifos exposure and perhaps even slow Parkinson's progression.

"The discovery that autophagy dysfunction drives the neurotoxicity also points us toward potential therapeutic strategies to protect vulnerable brain cells," says Bronstein.

The research has been published in Molecular Neurodegeneration.