Scientists are hard at work trying to assess the scale of our microplastic pollution problem and the likely health impacts. A new study now identifies several downstream health risks these tiny plastic fragments may pose as they traverse the environment.

Research suggests microplastics by themselves can be harmful to our biology, and they're also known to absorb other toxic pollutants.

Now, on top of this, new findings from researchers at the University of Exeter and the Plymouth Marine Laboratory in the UK suggest microbes also develop biofilms on top of microplastics.

These biofilms (or 'plastispheres') can harbor dangerous bacteria and aid their growth and survival – meaning microplastics might potentially be spreading pathogens and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) as well.

Related: Microplastics Linked to Worsening Alzheimer's Symptoms in Mice

That poses several serious health risks, from disease-causing bacteria finding their way into the food chain, to an increased spread of drug-resistant bacteria that make infections harder to treat and medical procedures more risky.

"Our research shows that microplastics can act as carriers for harmful pathogens and antimicrobial-resistant bacteria, enhancing their survival and spread," says marine scientist Pennie Lindeque, from the Plymouth Marine Laboratory.

"This interaction poses a growing risk to environmental and public health and demands urgent attention."

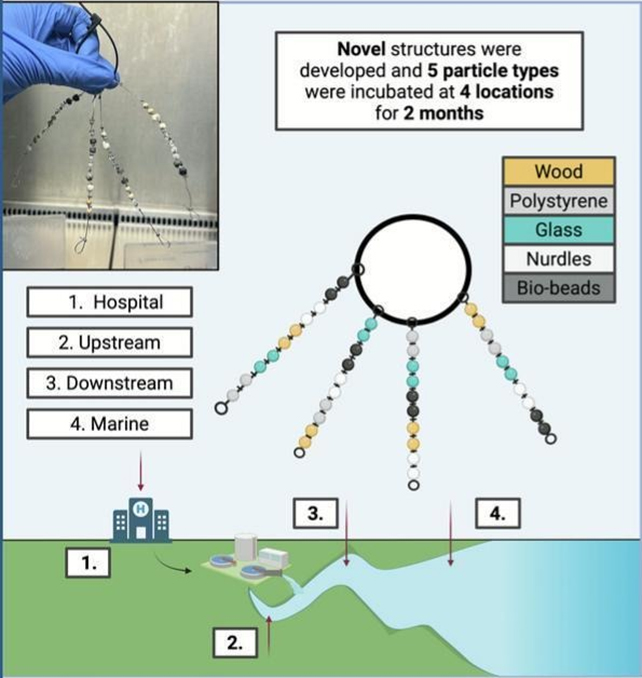

The researchers submerged strings of tiny plastic pellets used in manufacturing and water treatment, as well as polystyrene fragments of a similar size (around 4 mm), at four locations along the Truro river system in southwest England.

These sampling sites were chosen to cover a variety of expected water cleanliness levels, based on their proximity to a wastewater treatment plant and a hospital.

Small beads of glass and wood were also tested, along with plastic bio-beads used to host bacteria that help purify water. These bio-beads are intended to improve the environment – but not when they escape from treatment plants and leak into the river systems, as has happened several times in the past.

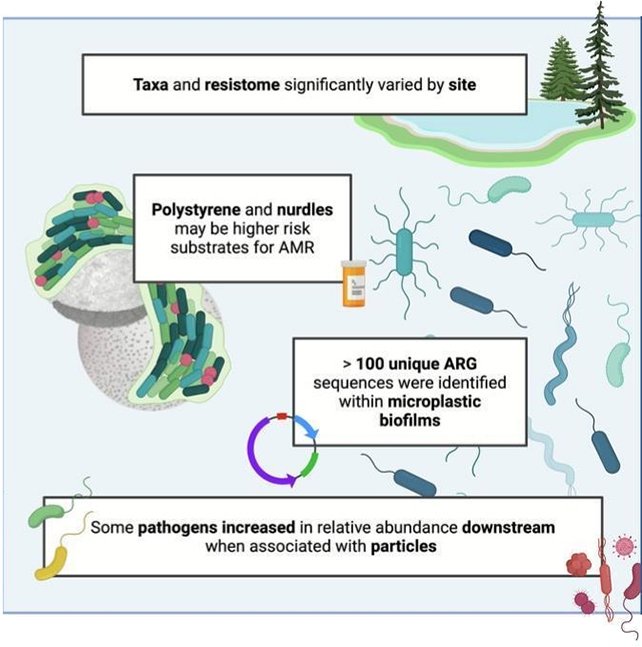

After two months, the team analyzed the bacteria that had gathered on the various materials. While the locations of the sampling sites influenced the makeup of resident bacteria more than the material type, the team did identify several problems with the plastic particles.

The biofilms that formed on microplastics carried significantly more genes from drug-resistant bacteria than those on wood or glass.

Harmful pathogens, including Flavobacteriia and Sphingobacteriia, were also more common on microplastics further downstream of the hospital and wastewater treatment plant, where those bacteria weren't particularly abundant in the water.

"Our research shows that microplastics aren't just an environmental issue – they may also play a role in the dissemination of antimicrobial resistance," says microbiologist Aimee Murray, from the University of Exeter.

"This is why we need integrated, cross-sectoral strategies that tackle microplastic pollution and safeguard both the environment and human health."

The researchers want to set up more sample sites and test a broader range of environmental conditions to see what the impacts might be. They also want to see more done to keep plastics – such as bio-beads – out of the environment.

It highlights that it's not just the toxic effects of microplastics we need to worry about, but also their capacity to act as bacteria breeding grounds – putting humans and wildlife alike at risk wherever plastics accumulate.

"This work highlights the diverse and sometimes harmful bacteria that grow on plastic in the environment," says marine scientist Emily Stevenson, from the University of Exeter, so "we recommend that any beach-cleaning volunteer should wear gloves during clean-ups, and always wash [their] hands afterwards."

The research has been published in Environment International.