Last year, astronomers discovered a massive supercluster of galaxies located approximately 4 billion light-years from Earth – and not only is it one of the largest known structures in the cosmos, it's also the most distant supercluster we've ever observed.

See, in space, everything is a question of perspective. From where you sit, the planet you're reading this on may seem like a pretty big deal, but it's only a tiny overall part of our Solar System, which in turn is basically an almost insignificant speck making up our galaxy, the Milky Way.

But we can still go bigger. Galaxies themselves are subsumed into larger stacks called galaxy groups and clusters – and then there are superclusters: unimaginably vast cosmic aggregations that collect galaxy clusters like a handful of spare change.

It's one of these handfuls that a team of astronomers in India has now identified, locating a previously unknown dense supercluster that they've named after the ancient Sarasvati River.

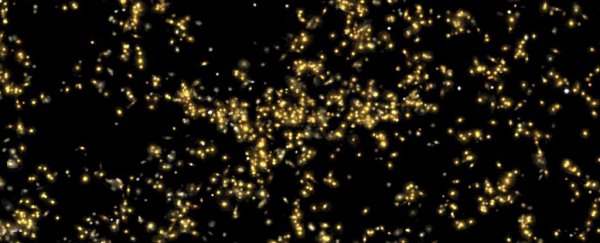

The Saraswati supercluster, discovered by researchers from the Inter University Centre for Astronomy & Astrophysics (IUCAA), spans an epic swathe of space measuring some 600 million light-years across – in which, the team estimates, lies the equivalent combined mass of over 20 million billion Suns.

(IUCAA)

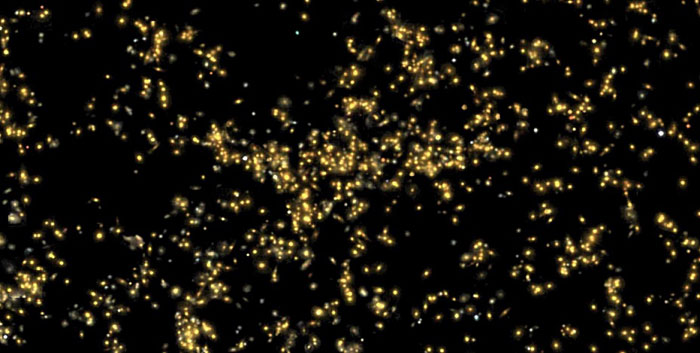

(IUCAA)

Aside from its stupendous size and mass, what makes the find so significant is that so far astronomers haven't actually identified that many superclusters, meaning Saraswati is joining the ranks of some pretty elite company.

"Previously only a few comparatively large superclusters have been reported," explain two of the team, astronomers Joydeep Bagchi and Shishir Sankhyayan, "for example, the 'Shapley Concentration' or the 'Sloan Great Wall' in the nearby Universe."

But what also sets Saraswati apart is its far-flung perch, sitting approximately 4 billion light-years away from you and me.

"It is the first time that we have seen a supercluster that is so far away," one of the team, Somak Raychaudhury, who also originally helped to identify the Shapley Concentration, told Shubashree Desikan at The Hindu.

"Even the Shapley is about 8 to 10 times closer."

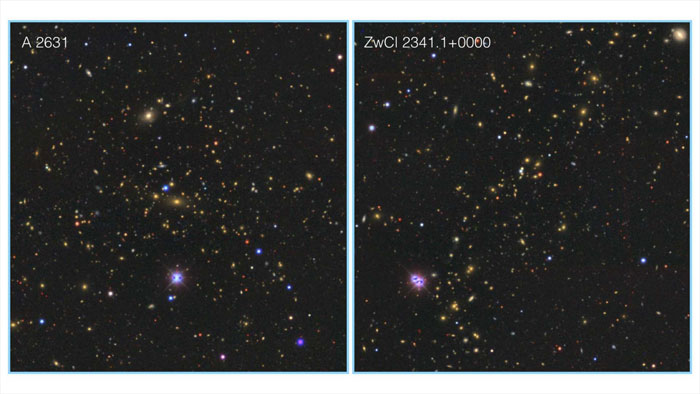

The two most massive galaxy clusters within in Saraswati supercluster. (IUCAA)

The two most massive galaxy clusters within in Saraswati supercluster. (IUCAA)

The researchers located Saraswati by examining data from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, and say that the supercluster contains at least 43 galaxy groups and clusters, comprising about 400 galaxies all up.

What's most exciting is that Saraswati's extreme distance from Earth means that the light we're seeing from has travelled an awfully long way to get here – and so shows us what the supercluster looked like when the Universe was only 10 billion years old.

Peering back in time like that could help us to understand how these massive superstructures come to be, and let us examine the conditions for their development in the early Universe.

"Since a structure of this vastness will only grow extremely slowly, taking many billions of years, it carries with it a sort of record of the entire history of its formation," Bagchi explained to New Scientist.

That said, Saraswati's looming presence 4 billion years ago did come as something of a surprise to the researchers, given our current understanding of galactic evolution suggests that superclusters would not have had enough time to form when the Universe was only 10 billions old..

What that could mean is that newer theoretical concepts – such as dark energy and dark matter, both of which scientists are still struggling to fully fathom – may have played a decisive role here.

"Theory has always been confounded by nature," Raychaudhury told The Hindu.

"It is true that the balance between dark matter and dark energy can produce large structures, but a supercluster of this size does present an enigma."

So while the Saraswati supercluster may have finally been revealed, it seems like an even larger, deeper truth still lies in check – just waiting to be discovered.

The findings were published in The Astrophysical Journal.

A version of this article was first published in July 2017.