Tiny air pollution particles may be doing more than harming our lungs. A new study links long-term exposure to PM2.5 to a higher risk of Alzheimer's disease, suggesting these particles could be affecting the brain more directly than scientists have assumed.

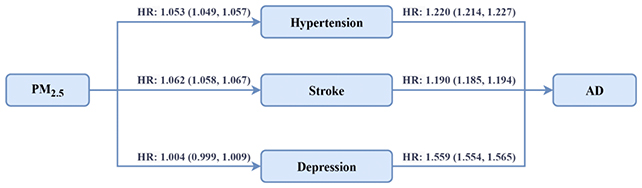

While air pollution has previously been linked with other conditions that might be driving Alzheimer's – including high blood pressure and depression – this research suggests that particulate matter could be contributing directly to some of the millions of new Alzheimer's diagnoses recorded each year.

The study comes from a team at Emory University in the US, and was designed to build on earlier research showing an association between PM2.5 in the air and neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's.

"Alzheimer's disease is the most common form of dementia and a growing public health challenge, especially in aging populations," write the researchers in their published paper.

"Our findings suggest that PM2.5 exposure was associated with increased Alzheimer's disease risk, primarily through direct rather than comorbidity-mediated pathways."

The researchers looked at health records for more than 27.8 million US citizens aged 65 and older across the course of 18 years, comparing medical conditions and diagnoses against estimated levels of air pollution, based on their local ZIP code.

Crucially, the link between exposure to higher levels of air pollution and an increased risk of Alzheimer's disease was a strong one, and remained notable even when other health problems were factored in.

"We examined 5-year average exposure immediately preceding disease onset and were unable to estimate exposures earlier in life due to the lack of historical exposure data," the authors explain.

"It is likely that the disease process began earlier, and our findings may therefore reflect the correlation of relatively recent exposure with past exposure levels."

In other words, rather than air pollution pushing up heart disease risk, and heart disease then pushing up Alzheimer's risk, for example, it seems air pollution can have its own effect on Alzheimer's risk.

This type of study is observational, so it doesn't show direct cause and effect between air pollution and Alzheimer's disease. It's also worth remembering that air pollution exposure was estimated from environmental data, not measured directly, and didn't take into account exposure inside people's homes or at work.

There was another interesting finding in the data, which was that those who had suffered a stroke were at a slightly higher risk of developing Alzheimer's disease. This suggests that strokes may make the brain more vulnerable to air pollution.

"The observed effect modification by stroke may reflect an underlying biological vulnerability in cerebrovascular pathways," write the researchers.

"Stroke-related neurovascular damage can compromise the blood–brain barrier, facilitating the translocation of PM2.5 particles or their associated inflammatory mediators into the brain."

We still don't know exactly what causes Alzheimer's, but it seems likely that many different contributors are involved. Each new study like this improves our understanding of what those contributors might be – and how effective preventative treatments could work.

There are likely to be numerous ways that fine particles can speed up neurodegeneration, the researchers suggest. They may include affecting brain tissue directly, elevating inflammation across the body, and the build-up of proteins linked to Alzheimer's.

Future research may be able to investigate these mechanisms more closely, but in the meantime, it seems that it's one of the many risk factors that contribute to Alzheimer's disease.

We know that the environments we live in can have major impacts on health in a wide variety of ways, and even more so in older age – when our bodies may not have the same level of defensive protection or the same restorative powers as they once had.

Related: Memory Loss in Alzheimer's Linked to Problems With The Brain's 'Replay Mode'

And of course, there are a multitude of reasons to want to cut down on air pollution, besides the association with Alzheimer's. It affects our mental well-being too, and worsens the effects of extreme heat waves, for example.

"Neighborhood environments that support healthy living are essential for sustainable, population-level disease prevention, including dementia," says psychologist Simone Reppermund from the University of New South Wales, who wasn't involved in the study.

"This influence is even greater in later life, when people spend more time in their local area due to retirement or poor health and are at higher risk of cognitive decline."

The research has been published in PLOS Medicine.